Acute or Recurrent Anteroinferior Glenohumeral Instability

Contents

- 1 Bullet points

- 2 Key words

- 3 History

- 4 Anecdote

- 5 Anatomical Considerations

- 6 Prevalence

- 7 Pathoanatomy and biomechanics

- 8 Natural History and Risk Factors of Dislocation or Recurrences

- 9 Natural History

- 10 Classification

- 11 Clinical Presentation and Essential Physical Examination

- 12 Apprehension

- 13 Scores

- 14 Essential Radiology

- 15 Treatments

- 15.1 Methods of Reduction

- 15.2 Conservative (Nonoperative) Treatment

- 15.3 Treatment of Acute First Traumatic Dislocations

- 15.4 Surgical (Operative) Treatment

- 15.4.1 Bankart and Associate Repairs

- 15.4.2 Remplissage

- 15.4.3 Surgical Technique

- 15.4.4 Subscapularis Tendon Augmentation or Capsular Reconstruction

- 15.4.4.1 Dynamic Anterior Stabilization (DAS)

- 15.4.4.2 Preoperative Patient Positioning

- 15.4.4.3 Initial Exposure and Portal Placement

- 15.4.4.4 Anterior Glenoid Preparation

- 15.4.4.5 Addressing the Long Head of Biceps and Subscapularis Split

- 15.4.4.6 Postoperative Rehabilitation

- 15.4.4.7 Latarjet

- 15.4.4.8 Arthroscopic Latarjet

- 15.4.4.9 Bristow

- 16 Rehabilitation

- 17 Results and Complications

- 18 References

Bullet points

- One of most common shoulder injuries, 1.7% annual rate in general population.

- High recurrence rate that correlates with age at dislocation, up to 80-90% in teenagers (90% chance for recurrence in age <20).

- Osseous lesions, either humeral or glenoid, are identified in 95.0%. The risk of failure of arthroscopic treatment is higher if not addressed. A glenoid bony defect of >20-25% is considered "critical" and is biomechanically highly unstable and require bony procedure to restore bone loss (Latarjet, Bristow, other sources of autograft or allograft).

- A Malgaigne (Hill Sachs) defect is a chondral impaction injury in the posterosuperior humeral head secondary to contact with the glenoid rim. It is present in 80% of traumatic dislocations and 25% of traumatic subluxations.

- Axillary nerve injury is most often a transient neurapraxia of the axillary nerve and is present in up to 5% of patients.

- Incidence of associated rotator cuff tears increase with age of 40 (30% at 40, 80% at 60).

- Static glenohumeral stabilizers are the bone, the ligaments, the capsule, the labrum, and the negative pressure. The dynamic ones are the rotator cuff and long head of biceps tendon.

- The labrum contributes to 50% of additional glenoid depth.

- Anterior static shoulder stability with arm in 90 degrees of abduction and external rotation is provided by the anterior band of inferior glenohumeral ligament (main restraint).

- The middle glenohumeral ligament provides static restraint with arm in 45° of abduction and external rotation.

- The superior glenohumeral ligament provides static restraint with arm at the side.

- The physical examination demonstrates instability if the apprehension test is positive, multidirectional hyperlaxity when the external rotation at side is equal or above 85 degrees, and a pathological laxity of the inferior glenohumeral ligament if the hyperabduction test is positive.

- Three views plain radiographs, including true anteroposterior of the glenohumeral joint, scapular Y (scapular lateral), and Velpeau axillary views are the mainstay of imaging in the setting of acute traumatic anterior instability. Plain radiographs including anteroposterior in neutral, internal and external rotations, scapular Y and Bernageau views are obtained for recurrent instability. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) arthrogram is useful to assess for labral or rotator cuff tears, computed tomography (CT) for bone loss assessment.

- Conservative treatment after the first traumatic anterior dislocation is recommended for patients who are not actively engaged in sports, above the age of 30 years old, with a low functional demand, with an associated humeral fracture, or for the athlete with an in-season shoulder dislocation.

- Rehabilitation consist of strengthening of dynamic stabilizers (rotator cuff and periscapular musculature), exercises for proprioception and other specific treatments if apprehension persist.

- Surgical treatment included Bankart repair, capsular plication +/- soft tissue procedures (such as remplissage or dynamic anterior stabilization (DAS) if < 20% bone loss.

- If bone loss ≥ 20%, bone reconstruction with Latarjet, Bristow or free bone block transfers such as Eden-Hybinette is recommended.

Key words

Anterior glenohumeral instability; shoulder dislocation; subluxation; reduction; bone loss; Malgaigne; Hill-Sachs; Bankart; capsular shift; remplissage; dynamic anterior stabilization (DAS); Latarjet; Bristow; free bone block transfer; Eden-Hybinette; complication; recurrence; pull-out.

History

The first recorded depictions of shoulder reduction are ancient.[1]

Egyptian hieroglyphs dated 3000 years earlier, pictorially depict a leverage method of shoulder manipulation, They have been followed by the Greeks and Romans. Around 400 BC, Hippocrates, the father of Western medicine, introduced the traction method to reduce the shoulder. [2][3][4]

In 1855, Malgaigne was the first one to describe the humeral bone loss also called Hill-Sachs lesion.[5]

In the 1890s, the understanding of the unstable shoulder was elucidated by the work of two French researchers, Broca and Hartman who introduced the concept of capsulolabral damage following dislocations as possible cause of recurrent instability. Notably, most of the findings considered current hallmarks of shoulder instability, including Bankart lesion, bony Bankart, Kim lesion, as well as anterior and posterior labral periosteal sleeve avulsions and glenoid avulsions of glenohumeral ligaments, were described in their papers, decades before the eponymous figures to whom they are now commonly assigned depicted them.[6]

In 1906, Perthes in Germany and a few years later, Bankart in the UK ascertained that the detachment of the labrum caused instability of the shoulder and emphasized reattachment of the labrum to stabilize the joint.[7][8]

Current free bone grafting techniques are based on the initial descriptions by Eden in 1918 and Hybinette in 1932 using autologous iliac crest.[9][10]

Due to donor site morbidity with autologous iliac crest bone grafting techniques, different auto- and allogeneic bone materials have been evaluated as alternatives. Open and arthroscopic approaches using distal clavicle, femoral head, distal tibial allografts or coracoid process are currently used. The first coracoid process transplant was probably realized by the German surgeon Noeske in 1921.[11]

Nowadays, two most popular bony procedures included the Latarjet and its variant, the Bristow.[12][13]

Anecdote

(unpublished data, courtesy of Gilles Walch) At the beginning of the 1950s, Albert Trillat, the head of the orthopedic surgical clinic at the Edouard Herriot Hospital in Lyon (France) and also the promoter of the "no touch technique", reported combination of an anterior labro-ligamentous complex reinsertion when feasible with a reduction of a so-called coraco-glenoid outlet by means of a coracoid osteoclasy and nail fixation (Figures).[14]

Another surgeon, Michel Latarjet, who was mainly active in the field of thoracic surgery, visited Dr. Trillat to learn the aforementioned technique. When Latarjet supposedly tried to reproduce the Trillat procedure, he carried an involuntary complete coracoid osteotomy. Thenceforth, not knowing what to do with the bony fragment, he fixed it to the anterior glenoid through the subscapularis using a screw. From this mishap was born the operation which now bears his name.[15]

Anatomical Considerations

The glenohumeral joint has six degrees of freedom with minimal bony constraint that provides a large functional range of motion. It thus renders this diarthrodial joint particularly vulnerable to instability. The glenohumeral joint is stabilized by dynamic and static structures. The dynamic stabilizers include the rotator cuff, the long head of the biceps, and the deltoid. The static stabilizers of the joint include the capsule, the glenohumeral ligaments, the labrum, negative pressure within the joint capsule, and the bony congruity of the joint. The superior glenohumeral ligament functions primarily to resist inferior translation and external rotation of the humeral head in the adducted arm. The middle glenohumeral ligament functions primarily to resist external rotation from 0 degree to 90 degrees and provides anterior stability to the moderately abducted shoulder. The inferior glenohumeral ligament is composed of two bands, anterior and posterior, and the intervening capsule. The primary function of the anterior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament is to resist anteroinferior translation.[16]

Prevalence

The glenohumeral joint is the most commonly dislocated large joint of the body, affecting approximately 1.7% of the general population.[17]

In greater than 90% of cases, the instability is anterior, has a traumatic origin, and occurs in young athletes involved in contact sports.[18][19]

Ongoing sports participation in this population is associated with a high recurrence rate.[20]

Pathoanatomy and biomechanics

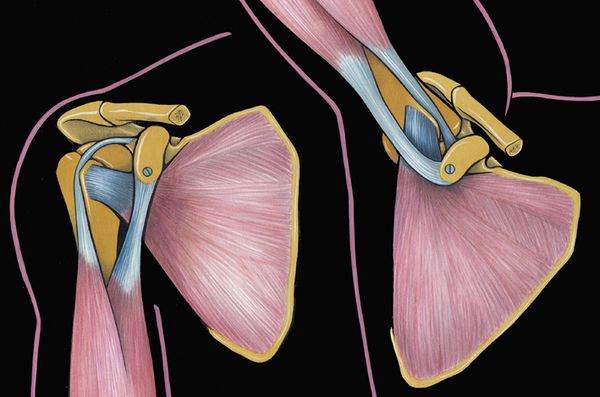

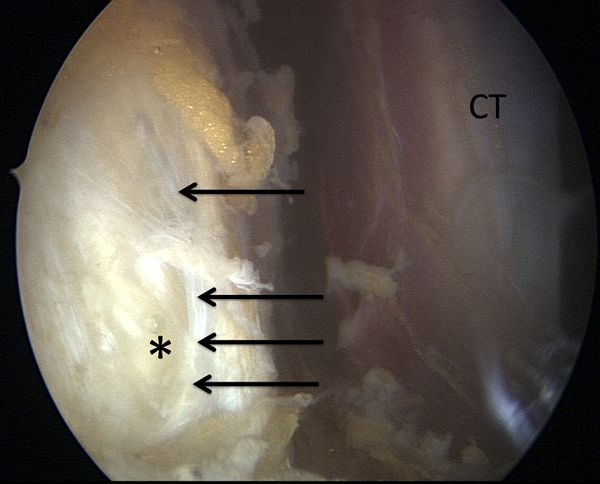

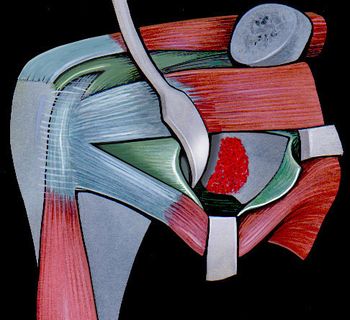

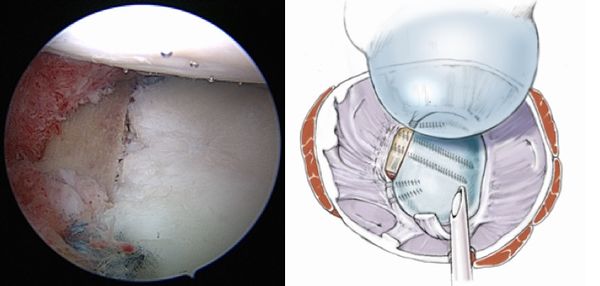

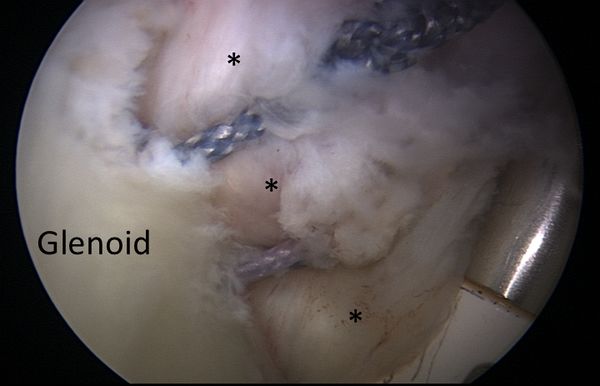

Anterior shoulder instability usually occurs with an anteriorly directed force applied to an abducted and externally rotated arm, or from a direct blow. During an anterior dislocation, many of the passive and active stabilizers may be damaged. The glenoid labrum, the glenohumeral ligaments, and the glenohumeral joint capsule, representing the soft tissue passive stabilizers will be injured; an avulsion of the anterior labrum, the classic Bankart lesion (Figure) or its variations (glenolabral articular disruption (GLAD), Perthes, anterior labroligamentous periosteal sleeve avulsion (ALPSA)) is almost invariably present,11,22,23 although it does not produce instability in isolation.[21][22][23][24]

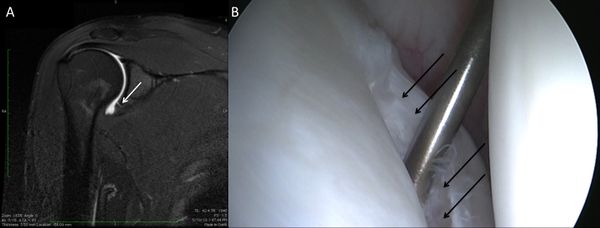

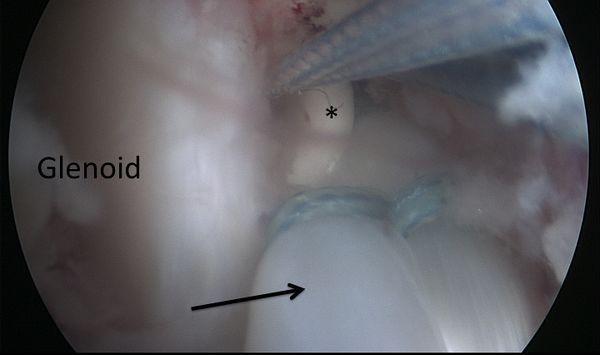

The anteroinferior glenohumeral ligaments and the capsule can be detached from the glenoid rim, and a plastic deformation of the glenohumeral ligaments or an HAGL lesion (Figure) are other common features.[25]

The plastic deformation of these structures becomes progressively more severe with subsequent episodes.[26][27][28]

The middle glenohumeral ligament functions to limit both anterior and posterior translation of the arm at 45 degrees of abduction and 45 degrees of external rotation whereas the inferior glenohumeral ligament resists translation of the arm in greater degrees of abduction.[29]

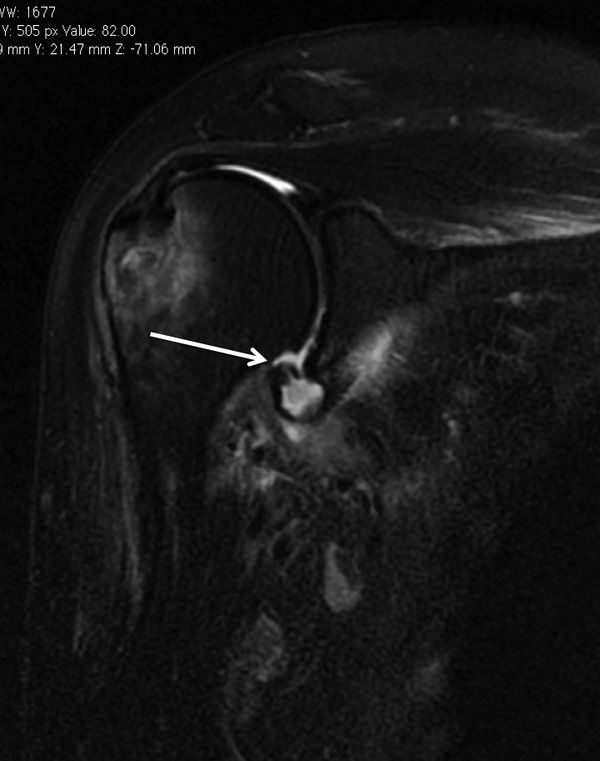

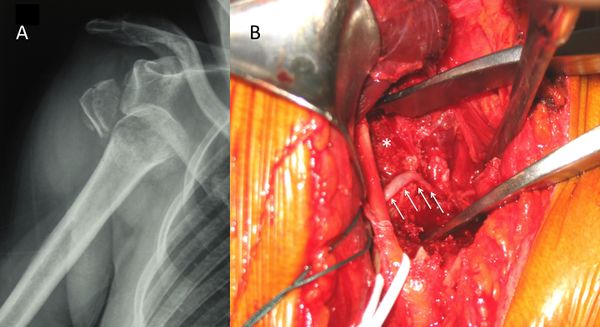

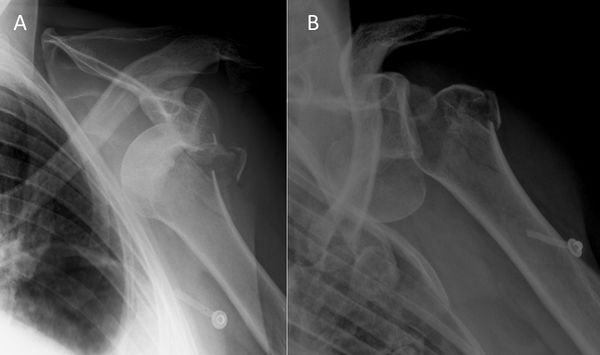

In addition to progressive soft tissue injury, recurrent dislocations can facilitate bony injury. Bony lesions are frequent in recurrent cases and may include defects of the glenoid (bony Bankart or beveling of the anterior glenoid resulting in loss of glenoid concavity), impaction of the posterolateral humeral head (Malgaigne lesion), or even coracoid or proximal humerus fractures (Figure).[30][31][32]

Given that the average glenoid diameter is about 24 mm, a 6 mm-wide or larger fragment of the glenoid will typically equate to a 25% or more of the articular surface and is considered a large bony fragment.[33][34]

Such significant glenoid bone loss can be viewed arthroscopically as an inverted pear configuration. All Malgaigne lesions are by definition engaging lesions (since it has engaged at least once). Thus, the notion of “engaging” versus “non-engaging” can lead to significant confusion. Some have proposed that the important lesions are those that engage in the 90-90 position.

Finally, the active restraint, mainly a lesion of the rotator cuff above the age of 40, will complete this complex situation.[35][36]

The glenohumeral joint is stabilized by a so-called “concavity compression” principle with the rotator cuff pulling the humeral head into the glenoid concavity and therefore ensuring stability through counteracting decentering translational forces.[37][38][39]

Natural History and Risk Factors of Dislocation or Recurrences

To understand the natural history of instability and its importance for the appropriate management of this pathology, the following questions should be answered: What happens in the shoulder after the first dislocation? Which structures suffer damage? Who are the patients at higher risk of recurrence? How does the disease evolve without treatment? Will surgical treatment avoid future negative outcomes and prevent degenerative joint disease? Who should we treat and when?[40]

80% of anterior-inferior dislocations occur in young patients. Recurrent instability is common and multiple dislocations are the rule. Instability is influenced by a large number of variables, including age of onset, activity profile, number of episodes,delay between first episode and surgical treatment. The different risks factors are:

-Young males, (up to 100% of recurrence)[41][42]

-Practice of contact sports, forced overhead activity,

-Sport practice at a competitive level,[43]

-Bony impairment,

-Concomitant hyperlaxity.[44]

Natural History

Classification

Instability can be classified as primary or recurrent. The latter can be further classified as dislocation, subluxation, apprehension, or an unstable painful shoulder. In frank dislocation, the articular surfaced of the joint are completely separated. Subluxation is defined as symptomatic translation of the humeral head on the glenoid without complete separation of the articular surfaces. Apprehension is classically defined by fear of imminent dislocation in the 90-90 position. This could correspond to an instability phenomena or a persistent fear after a successful glenohumeral stabilization (please refer to Apprehension chapter).[45]

The unstable painful shoulder presents as pain only (as opposed to a sense of instability) during an apprehension maneuver at clinical examination.[46][47]

The majority of these patients has a history of trauma, but simply do not report a clear history of trauma. Careful preoperative and/or arthroscopic examination will show that the majority of these patients also have evidence of instability (i.e. labral tear, glenoid fracture, or Malgaigne (Hill-Sachs) lesion)

Five types of traumatic anterior dislocation have been described. The subcoracoid dislocation has an antero-inferior direction and is the most common. Other types, including subglenoid, subclavicular, retroperitoneal, and intrathoracic are rare and usually associated with severe trauma.[48][49]

Osseous defects of the anterior glenoid rim can be classified into three types according to their pathomorphology. In particular, acute (type I) and chronic glenoid rim defects (type II and III) are differentiated, which are provoked either by an acute glenoid fracture or recurrent shoulder dislocations with subsequent erosion of the glenoid rim. Type I lesions are further divided into bony Bankart lesions (type Ia), solitary glenoid rim fractures (type Ib) and multifragmented glenoid rim fractures (type Ic). In most cases, type I glenoid defects can sufficiently be reconstructed by mobilization and anatomical refixation of the fragment.

In cases of complex multifragmented glenoid rim fractures (type Ic), however, it may be necessary to resect the fragments and augment the glenoid defect. Type II defects include chronic fragment-type of lesions that are characterized by an extra-anatomically consolidated or pseudarthrotic fragment of insufficient dimensions for a defect reconstruction due to resorption processes. A bony glenoid augmentation may be indicated, depending on the dimensions of the glenoid defect and the remaining fragment. Erosion-type of defects (type III) are predominantly observed in patients with recurrent anterior shoulder dislocations. These usually develop on the basis of a glenoid fracture with subsequent resorption of the fragment, or as a result of chronic abrasion of the anterior glenoid rim. If the bone loss adopts substantial dimensions, mere soft-tissue stabilization procedures are not sufficient in re-establishing stability.

Clinical Presentation and Essential Physical Examination

The history should document age, hand dominance, occupation, participation in sporting activities, initial mechanism of the injury, the position of the arm (extension, abduction, and external rotation favors anterior dislocation), how long the shoulder stays out, the method of reduction, the number of recurrences (frank dislocation vs subluxation), and the effectiveness of a previous nonoperative or operative treatment. The diagnosis of recurrent traumatic anterior glenohumeral instability is usually made easily on the basis of the history, radiographs, and a positive apprehension sign. However, when collision athletes are seen, care should be taken because they may not experience clear dislocation or subluxation and only complain of pain or weakness.

A comprehensive physical examination is essential. The aim is to define the direction of instability, the presence of an associated pathologic hyperlaxity, and to exclude neurological and rotator cuff impairment. Passive and active glenohumeral range of motion should be assessed. Rotator cuff examination includes strength tests such as belly-press, bear hug, Jobe tests and strength in external rotation again resistance (please refer to Rotator Cuff Pathology/Rotator cuff complete lesion). Tests for anterior and superior labral lesions are not systematically perform as they have a poor sensitivity and specificity.[50]

The neurovascular status of the upper extremity is assessed, particularly with regard to the axillary nerve since there is a high incidence of injury to this nerve with traumatic instability (Figure).

Laxity is a normal, physiologic and asymptomatic finding, that corresponds to translation of the humeral head in any direction to the glenoid.[51]

Laxity is assessed with the sulcus sign, anterior-posterior drawer, hyperabduction tests, and external rotation elbow at side. The two former tests are only qualitative and are not routinely performed by the authors. Hyperlaxity is constitutional, multidirectional, bilateral and asymptomatic. Hyperlaxity of the shoulder is probably best defined as external rotation elbow at the side equal or greater than 85 degrees.[52]

This non-pathological finding is a risk factor for instability but does not by itself demand treatment unless there is clear pathological laxity. Pathological laxity of the inferior glenohumeral ligament is observed when passive abduction in neutral rotation in the glenohumeral joint is above 105 degrees, there is apprehension above 90 degrees of abduction, or if a difference of more than 20 degrees between the two shoulders is noted.[53][54]

For apprehension the patient is initially invited to demonstrate his or her functional problem to the examiner (no-touch examination). This examination alone, coupled with a good history, often provides the information needed. However, if the direction of the instability remains unclear, the apprehension (crank) test, an abducted and externally rotated position suggestive of anterior instability is performed. Fear of dislocation or a feeling of anterior pain is considered positive for damage to the anterior capsulolabral complex, which should be relieved with posterior translation of the humerus (relocation maneuver). To summarize, the physical examination demonstrates instability if the apprehension test is positive, multidirectional hyperlaxity when the external rotation at side is equal or above 85 degrees, and a pathological laxity of the inferior glenohumeral ligament if the hyperabduction test is positive.

Apprehension

Apprehension can be difficult to diagnose pre- or post-operatively, as it seems more complex than a pure mechanical problem of the shoulder. Although clinical definition seems to be well established, its underlying pathologic mechanism remains unclear. This may explain the wide reported range (3% to 51%) of patients with ongoing apprehension or who will avoid any shoulder movement after an open or arthroscopic stabilization, despite a clinically stable joint.[54][55][56]

Failure to recognize and adequately address this issue may result in poor outcome and lead to unnecessary surgery or even revision. Furthermore, identifying this condition may allow establishing adequately targeted rehabilitation programs.

Definition

An important aspect to incorporate in dislocation management is apprehension, defined as anxiety and motor resistance in patients with a history of anterior glenohumeral instability. Clinically, apprehension sign is defined as fear of imminent dislocation when placing the arm in abduction and external rotation, and should be distinct from mere pain which can be related to inflammation, stiffness and other shoulder pathologies.[57][58]

Proprioception, as defined by Charles Scott Sherrington, is the sense of the relative position of neighboring parts of the body and strength of effort being employed during movement.[59]

It is distinct from exteroception, by which one perceives the outside world, and interoception, by which one perceives pain, hunger, or the movement of internal organs. The brain integrates information from proprioception and from the vestibular system into its overall sense of body position, movement, and acceleration. Kinesthesia refers either to the brain's integration of proprioceptive or vestibular inputs.

“Localization” of Apprehension

The pathogenesis of apprehension is not fully understood. Theoretically, apprehension could be related to:

1) Brain changes induced by dislocations[60][61][62][63]

2) Peripheral neuromuscular lesions consecutive to dislocation affecting proprioception[64]

3) Persistent mechanical instability consisting in micro-motion[65]

Brain

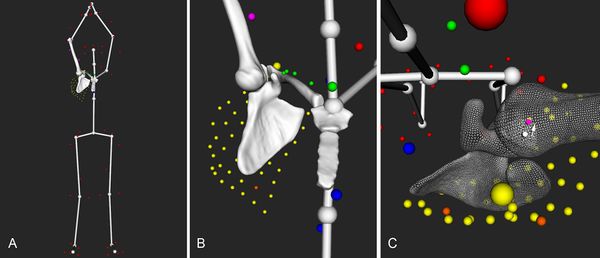

Fear, anxiety and anticipation of situations that could lead to a dislocation are essential cognitive processes in shoulder apprehension. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) measures brain activity by detecting changes associated with blood flow.[66]

When exploring neuronal connections and cerebral changes induced by shoulder dislocation, research revealed that several cerebral areas are modified, representing the different aspects of shoulder apprehension. Specific reorganizations are found in apprehension-related functional connectivity of the primary sensory-motor areas (motor resistance), dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (cognitive control of motor behavior), and the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex/dorsomedial prefrontal cortex and anterior insula (anxiety and emotional regulation) (Figure).[67]

Those regions are involved in the cognitive control of motor behavior. Hence, there is motor control anticipation and muscular resistance (protective reflex mechanism), in order to avoid shoulder movement that could lead to dislocation.[68]

Fractional anisotropy, representing white matter integrity, is increased in the left internal capsule and partially in the thalamus in patients compared to healthy controls. Fractional anisotropy correlated positively with pain visual analog scale (VAS) scores (p < .05) and negatively with simple shoulder test (SST) scores (p < .05).[69]

This suggests an abnormal increased axonal integrity and therefore pathological structural plasticity due to the over-connection of white matter fibers in the motor pathway. These structural alterations affect several dimensions of shoulder apprehension as pain perception and performance in daily life.

Shoulder stabilization could allow the brain to partially “recover”. Patients with shoulder apprehension underwent clinical and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) examination before and one year after shoulder stabilization surgery. Clinical examination showed a significant improvement in postoperative shoulder function compared with preoperative. Coherently, results showed decreased activation in the left pre-motor cortex postoperatively, demonstrating that stabilization surgery induced improvements both at the physical and at the brain level, one year postoperatively (Figure). Most interestingly, right–frontal pole and right-occipital cortex activity is associated with good outcome in shoulder performance.[70]

Peripheral Neuromuscular Lesion

During a traumatic dislocation, there are a disruption of the shoulder tendinomuscular (in 10% of cases) and peripheral nerve lesions (in 14% of cases).[71]

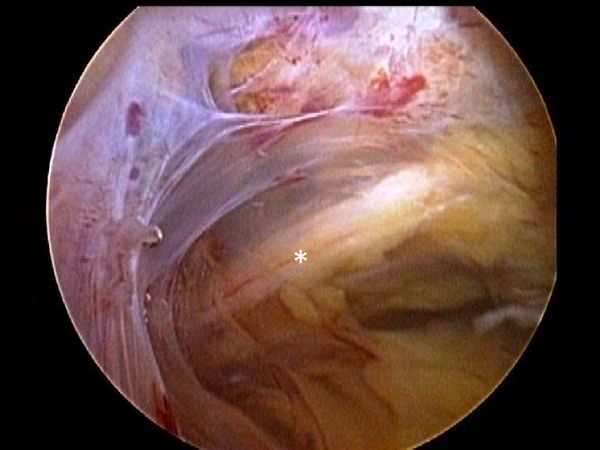

However, this does not account for subclinical neurologic damage that may be much more preponderant. Capsuligamentous structures surrounding the glenohumeral joint are richly innervated with proprioceptors and therefore play an important sensorimotor role in addition to their primary mechanical stabilizising function. Thus, when considering the extensive and frequent damage to these structures after shoulder dislocation (Figure), there is bound to be an important loss in glenohumeral proprioception.[72][73]

The latter plays a significant role in stabilization of a normal healthy shoulder and after any shoulder injury by contributing to motor control.[74]

Surgical stabilization has been shown to help proper healing of these structures and thus restoring proprioception of the glenohumeral joint.[75]

Glenohumeral Joint

The third etiologic factor for apprehension is persistent micro-motion in the glenohumeral joint despite a clinically stable shoulder, satisfactory radiographic results, and no new episode of subluxation or dislocation. Shoulder dislocation causes damage to the capsuloligamentous complex in 52% of the cases, and the glenoid labrum in 73% of the cases.[76][77]

The plastic deformation of these structures becomes progressively worse with subsequent episodes.The plastic deformation of these structures becomes progressively worse with subsequent episodes. In addition to progressive soft tissue injury, recurrent dislocations induce bony lesions, which may involve the glenoid (bony Bankart), the posterolateral humeral head (Malgaine), or both. Severity of apprehension, quantified as the moment at which it appears during the course of abduction and external rotation, seems to be correlated to the extent of bone loss. Capsular redundancy has also been recognized as a risk factor for ongoing apprehension after surgical stabilization and Ropars et al. found a significantly decreased apprehension in patients with associated capsulorraphy to Latarjet procedures, compared with patients with Latarjet and no capsular reconstruction.[78]

However, these changes may be very subtle and therefore not detectable on standard clinical magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in neutral position. This has been described by Patte et al. in non-operated patients and popularized under the name of "unstable painful shoulder".[79][80]

This micro-motion may yet still be present after surgical stabilization. Shoulder stabilization may thus only prevent new episodes of dislocation, rather than actually truly stabilizing the shoulder.[81][82]

A study described glenohumeral translation in patients with traumatic anteroinferior instability and subsequently analyzed the effect of glenohumeral stabilization on this translation. For all movements, the authors recorded humeral head position of the contralateral and ipsilateral shoulders in relation to the glenoid center pre- and 1 year post-operatively. They observed an anterior translation of the humeral head (Figure), especially during flexion and abduction movements (p < .05 and p < .05, respectively). One year after surgery, all patients had a clinically stable shoulder and none presented with a new episode of dislocation or subluxation.

However, anterior translation of the humeral head was not significantly reduced and remained close to preoperative values confirming that shoulder stabilization does not stabilize the shoulder but uniquely prevents further dislocation. These findings have several important implications. First, it may explain residual pain, apprehension, and impossibility to return to sport at the same level as reported in other studies. Second, persistent abnormal motion between the glenoid and the humeral head might be the underlying cause of dislocation arthropathy that is observed with a prevalence of 36%. Repeated sliding of the humeral head against the glenoid associated with degenerative changes of cartilage properties and decreased biological healing potential related to aging, could lead to a vicious circle of extensive cartilage damage.[83]

Scores

Rowe

This subsection does not exist. You can ask for it to be created, but consider checking the search results below to see whether the topic is already covered.

Walch-Duplay

This subsection does not exist. You can ask for it to be created, but consider checking the search results below to see whether the topic is already covered.

WOSI

This subsection does not exist. You can ask for it to be created, but consider checking the search results below to see whether the topic is already covered.

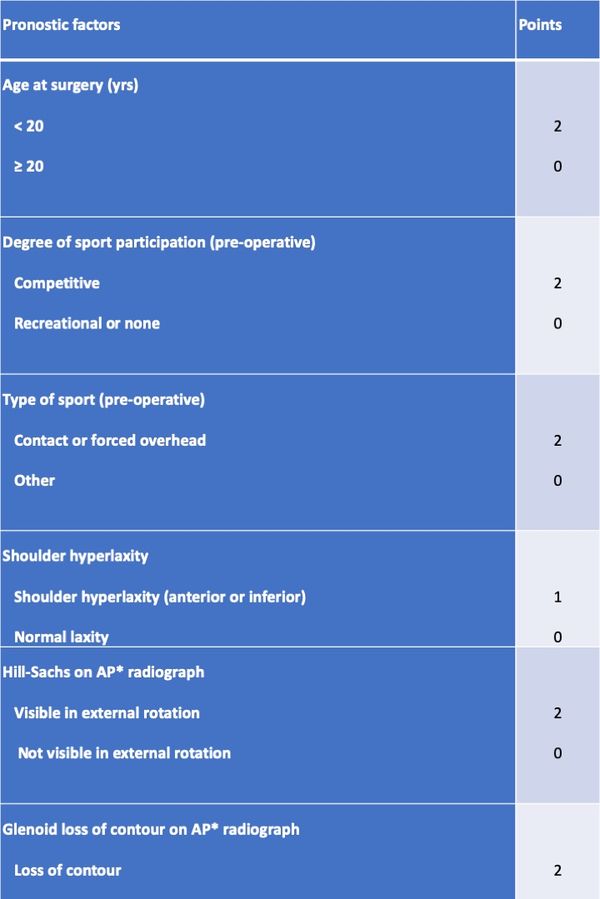

ISIS

Boileau et al. proposed a simple 10-point scale scoring system (instability severity index score (ISIS)) based on factors derived from a pre-operative questionnaire, physical examination, and anteroposterior radiographs to determine the risk of treatment failure following isolated arthroscopic Bankart repair (Table). In this model an ISIS of 3 or less was associated with a 5% rate of recurrence, a of 4 to 6 was associated with a 10% rate of recurrence, and an ISIS over 6 was associated with a 70% rate of recurrence. Although it has imperfections, this score, validated since, has merit to easily remind the clinician of factors that are important to consider when evaluating a patient.[84][85]

Table: The instability severity index score is based on a pre-operative questionnaire, clinical examination, and radiographs.

Essential Radiology

Radiographic evaluation is based on whether the dislocation is acute or chronic.

Acute Dislocation

Three views plain radiographs, including true anteroposterior of the glenohumeral joint, scapular Y (scapular lateral), and Velpeau axillary views are the mainstay of imaging in the setting of traumatic anterior instability[86]

The latter view is crucial to obtain, as the two first alone do not allowed to exclude a dislocation. The goal is to confirm the direction of dislocation and to evaluate associated lesions. One reduced, further imaging studies in the setting of an associated fracture (computed tomography (CT)), suspicion of rotator cuff injury (ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)), or vascular impairment (injected CT) may be warranted.

Preoperative Planning in Case of Recurrent Dislocation

The first step is to analyze, if available, plan radiographs with the shoulder out of joint to confirm the direction of instability. Plain radiographs including anteroposterior in neutral, internal and external rotations, scapular Y and Bernageau views are then obtained.[87]

Bone loss, static instability, post-dislocation arthropathy, and coracoid non-union (if a Latarjet or a Bristow procedures are planned) have to be estimated. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) arthrogram is useful to assess for soft tissue such as an anterior labral tear (Figure).

Associated intra-articular pathology such as SLAP, HAGL, and rotator cuff lesions or a paralabral cyst are also assessed (Figure).

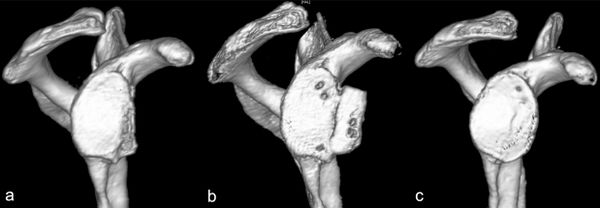

The evaluation is completed by a 3D computed tomography (CT) arthrogram in the setting of recurrent instability in which there is primary concern for bone loss. The extent of both glenoid bone loss and Hill-Sachs lesions are best assessed by computed tomography (CT) scan and are used to determine the need for a bony procedure as opposed to arthroscopic Bankart repair (Figures).

Treatments

The degree, nature and combination of injuries induced by traumatic glenohumeral instability are highly variable. Damage to the bony and soft tissue stabilizers of the shoulder, as well as neurologic impairment, must be detected and analyzed in order to provide the patient with the most adequate treatment option. This new knowledge should be applied to rehabilitation therapy and surgical stabilization techniques. As the current stabilization techniques do not seem to prevent residual glenohumeral micro-motion, it remains to be determined which factors help to minimize this phenomenon, whether it is, the increase in the anteroposterior diameter of the glenoid with a bone graft, the sling effect provided by the conjoined tendon or the long head of the biceps, the capsulorraphy, the repaired labrum or the remplissage.[88][89][90][91]

Methods of Reduction

Around 400 BC, Hippocrates, the father of Western medicine, introduced the traction method to reduce the shoulder. The patient lay supine whilst the physician standing on the patient's affected side held the arm and applied traction. The stockinged foot of the physician placed in the axilla served as counter traction. This technique was detailed in the Hippocratic Corpus, and as it remained the primary medical text for centuries so did the method. Similar technique of reduction was re-introduced in the 1870 as a painless technique by Theodor Kocher, but is now obsolete because of the likelihood of serious complications.[92]

Conservative (Nonoperative) Treatment

Heading towards a better understanding of the complex and multifactorial origins of glenohumeral instability and apprehension, postoperative management may in turn also be improved, notably in challenging cases of patients with persistent apprehension, despite a clinically stable shoulder. Knowing that shoulder apprehension could be the result of ongoing cerebral abnormalities or residual micro-motion may avoid costly series of onerous investigations, useless physiotherapy sessions or even re-operations. Furthermore, this perspective offers a new angle of a therapeutic approach that differs from conventional manual rehabilitation methods centered on the glenohumeral joint itself. If persistent apprehension or micro-motion is detected, growing research evidence supports the use of a multidisciplinary approach including:

1) A "reafferentation" (reconveying and connecting the neurological peripheral input to the cortex)89 of the shoulder particularly focused on proprioceptive work,69 which has been proved to lead to superior neuromuscular control than strengthening alone.[93][94][95]

2) A biofeedback therapy where the patient directly visualizes his abnormal response to a negative stimulus on fMRI or electroencephalogram, and can thereby actively correct it. This treatment modality has already shown to improve shoulder control and performance in various settings,[96][97][98]

3) a cognitive behavioral approach to decondition this pathological residual apprehension by making them realize residual apprehension does not necessarily lead to recurrent instability with gradual exposition that has already shown successful results in the treatment of kinesiophobia,94-96 a condition based on a re-injury fear-avoidance model initially described in low-back pain,97 further popularized in sports medicine98 and various upper limb conditions.[99]

4) Electric stimulation of hypoactive rotator cuff and periscapular muscles.[100]

Treatment of Acute First Traumatic Dislocations

The first step, whenever possible, is to obtain a complete set of radiographs before attempting a reduction. This will allow an assessment of the type of dislocation and associated bone injuries. Attempting to reduce a fracture dislocation can have troublesome clinical and legal consequences (Figure).

Exceptions are an impossibility to have reasonably fast access to radiology or a patient with neurological impairment. Because of the possible association of nerve injuries and, to a lesser extent, vascular injuries (Figure), an essential part of the physical examination is an assessment of the neurovascular status of the upper extremity before reduction.[101][102]

They are numerus appropriate methods of reduction that have been described. The second step is to use the technique of closed reduction which is mastered by the doctor who will perform the maneuver. The glenohumeral joint should be reduced as gently and expeditiously as possible. In the case of fracture dislocation, the reduction is best performed under general anesthesia to have adequate muscle relaxation. After reducing the dislocation, plain radiographs are obtained to verify the adequacy of the reduction.

Results concerning conservative treatment are still debatable. A stable shoulder is obtained at ten years in only half of patients with conservative treatment.[103]

However, recurrence rate is highly dependent on age and activity of the patient; studies have reported a 72% to 95% recurrence in patients under 20 years of age, and 70% to 82% recurrence between the ages of 20 and 30 years, and only 30% in those over 30 years of age.[104][105][106]

Many patients above the age of 30 would consequently undergo unnecessary surgery if proposed after the first dislocation. Conservative treatment after the first traumatic anterior dislocation may be thus recommended for patients who are not actively engaged in sports, above the age of 30 years old, with a low functional demand, with an associated humeral fracture, or for the athlete with an in-season shoulder dislocation. For the latter situation, athletes are allowed to attempt to return to competition provided there is enough time left in the season to permit adequate rehabilitation with progression to sport-specific drills.

Rehabilitation, including return of range of motion and strengthening of dynamic stabilizers may facilitate return to sport within several weeks. Motion-limiting braces that prevent extreme shoulder abduction, extension, and external rotation are often prescribed as it may reduce the risk of recurrence. However, such braces are not well-tolerated in patients who must complete certain overhead tasks such as throwing. Moreover, a second in-season shoulder dislocation should lead to removal from sport and proceeding with stabilization so as to avoid further glenohumeral damage.

A number of studies have compared nonoperative treatment and arthroscopic stabilization. Overall, these studies report a sevenfold reduction in the risk of recurrent instability after arthroscopic stabilization, when compared with nonoperative treatment for the first-time dislocator.[107]

A Cochrane review concluded that early surgical intervention is warranted in young adults aged less than 30 years engaged in highly demanding physical activities.[108]

Consequently, for patients who are actively engaging in a collision or contact or overhead sport, who risk their life in case a new dislocation (e.g. firemen, proponents of extreme sports like base jumping, and climbing), with associated static anterior subluxation, an interposed tissue or a nonconcentric reduction, or patients with rotator cuff avulsion, conservative measures are usually inadequate and prompt surgery is indicated.

Surgical (Operative) Treatment

Recurrent dislocation is not trivial. Each episode creates new lesions and increases the risk of developing dislocation arthropathy. The concept of early operative surgical management of the first-time dislocator has consequently been introduced to address the high recurrence rate in the young athletic population. A surgery should be proposed, as having the ultimate aim to achieve a pain-free stable shoulder while preserving range of motion. The surgical approach is based on the extent of bone loss and patient-specific risk factors for recurrence.

Bankart and Associate Repairs

The aim of a Bankart repair is to restore anatomy by reattaching the labrum to the glenoid (Figure) and tighten the inferior glenohumeral ligament by shifting from inferior to superior. Several technical factors are also important to success. It is important to place anchors at the margin of the articular surface (as opposed to the glenoid neck) to allow recreation of the labral bumper. The surgeon must be sure to obtain a proper inferior to superior shift of the capsule (Neer’s modification). Although this surgery can be performed in an open manner, the advantage of an arthroscopic approach is that it preserves the subscapularis and allows assessment of associated pathology. The literature demonstrates that patients with low risk of recurrence will benefit from either an anatomic open or arthroscopic repair with an acceptable rate of recurrence.[109]

HAGL (Humeral Avulsion of the Glenohumeral Ligaments) lesions are uncommon causes of anterior instability. There are 3 variants of HAGL lesions: 1. Avulsion from bone 2. Capsular split 3. Combined bone avulsion and capsular split. These lesions can be can be addressed by repair or more easily by a Latarjet.

Remplissage

Remplissage has been described by Connoly123 and may be used as an adjunct to arthroscopic Bankart repair in the setting a of large Malgaigne (Hill-Sachs) lesion with glenoid bone loss of <25%.[110]

This technique consists of a posterior capsulodesis and infraspinatus tenodesis that fills the Malgaigne lesion. The purpose is to render the Malgaigne lesion extra-capsular, avoiding its engagement. Wolf et al. and Boileau et al. presented encouraging mid- to long-term results of arthroscopic remplissage and concomitant anterior Bankart repair.[111][112]

Surgical Technique

The arthroscope can typically remain in the posterior portal because the 70 degrees angle enhances appropriate visualization. Depending on patient anatomy, the arthroscope can be switched to the anterolateral portal to obtain another view of the defect. A spinal needle is centered over the Malgaigne (Hill-Sachs) lesion, and an accessory posterolateral portal is created 2 fingerbreadths lateral to the posterior viewing portal to allow orthogonal insertion of suture anchors. The use of a cannula is optional. A shaver is used to abrade the Malgaigne (Hill-Sachs) lesion. Two anchors are inserted in the valley of the defect adjacent to the articular margin, 1 superior and 1 inferior. If used, the cannula is at this point retracted into the subdeltoid space. A curved penetrating grasper is used to retrieve the inferior anchor suture, followed by a straight penetrating grasper for the superior anchor suture. The humeral head is reduced, and the inferior sutures are tied in mattress fashion in the subdeltoid space, followed by the superior sutures, to complete the remplissage.

Subscapularis Tendon Augmentation or Capsular Reconstruction

When traditional arthroscopic Bankart repair is not possible due to severe capsulolabral deficiency, different types of open or arthroscopic subscapularis tendon augmentation or capsular reconstruction have been described.[113][114][115][116]

Surgical technique

A standard diagnostic arthroscopy is performed with a 30 degrees arthroscope, viewing through a posterior portal with a pump maintaining pressure of 50 mm Hg. The labrum is inspected in its entirety. An anterior portal is established just above the lateral half of the subscapularis and medial to the sling of the biceps, by use of an 18-gauge spinal needle with an outside-in technique. An anterosuperolateral portal is similarly established off the anterolateral border of the acromion. This portal should be placed so that it provides a 45 degrees angle of approach to the superior glenoid. The arthroscope is placed in the anterosuperolateral portal, and the anterior labrum is more thoroughly inspected. The remaining capsulolabral sleeve is dissected from the glenoid neck with an arthroscopic elevator until the subscapularis muscle is visible deep to the cleft. A 2- to 3-mm strip of articular cartilage is removed along the glenoid rim with a ring curette, creating an enhanced bone bed for capsulolabral repair. A capsulolabral repair is performed inferiorly with whatever good tissue remains. An anteroinferior anchor is placed. After placement of this anchor, if there is insufficient capsulolabral tissue to create the desired “bumper” along the anterior glenoid rim, the surgeon must consider various reconstructive options, including a split subscapularis tendon flap.

Augmentation With Split Subscapularis Flap

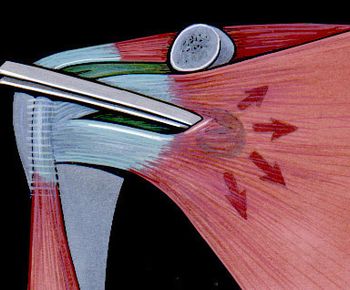

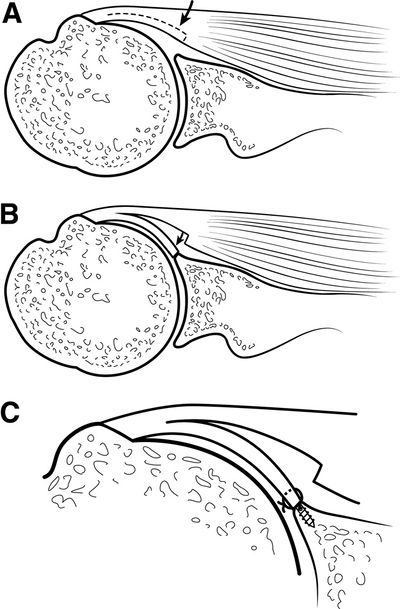

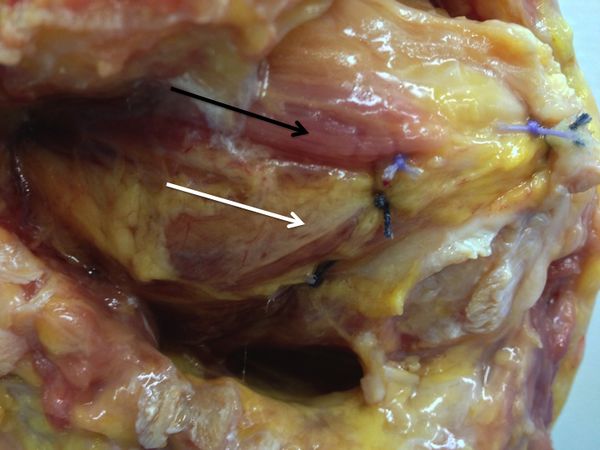

To augment the capsulolabral deficiency, a flap of the posterior portion of the superior half of the subscapularis tendon is mobilized and undergoes tenodesis to the anterior glenoid. This flap is created in a “trapdoor” fashion such that the capsular surface of the subscapularis tendon is reflected from medial to lateral as a separate lamina while the outer surface in left unaltered. By use of arthroscopic scissors introduced through the anterior portal, a longitudinal incision through one-half the thickness of the subscapularis is created in the superior half of the tendon (Figure).

Care is taken not to violate the full thickness of the subscapularis. The subscapularis flap dissection progresses from medial to lateral until the leading medial edge of the flap is mobile enough to reach the anterior glenoid. After mobilization of the subscapularis tendon flap, additional suture anchors are placed on the previously prepared glenoid strip at the 3-o'clock and 4-o'clock positions. Sutures from the anchor are passed through the subscapularis flap and tied as described previously. This completes the augmentation with a split subscapularis tendon flap (Figure).

Postoperatively, the patient's extremity is placed in a sling for 6 weeks. At the end of 6 weeks, stretching exercises are commenced with full forward flexion allowed and external rotation to half that of the contralateral shoulder. The goal is to achieve half the external rotation of the normal side at 3 months postoperatively. Strengthening is delayed until 4 months postoperatively because this is usually a last-resort salvage procedure. Return to full activities is delayed until 1 year postoperatively.

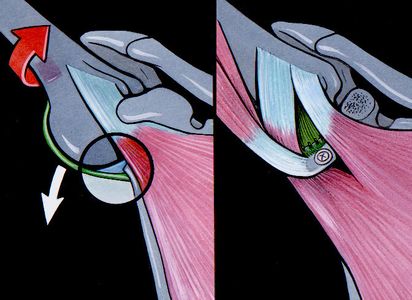

Dynamic Anterior Stabilization (DAS)

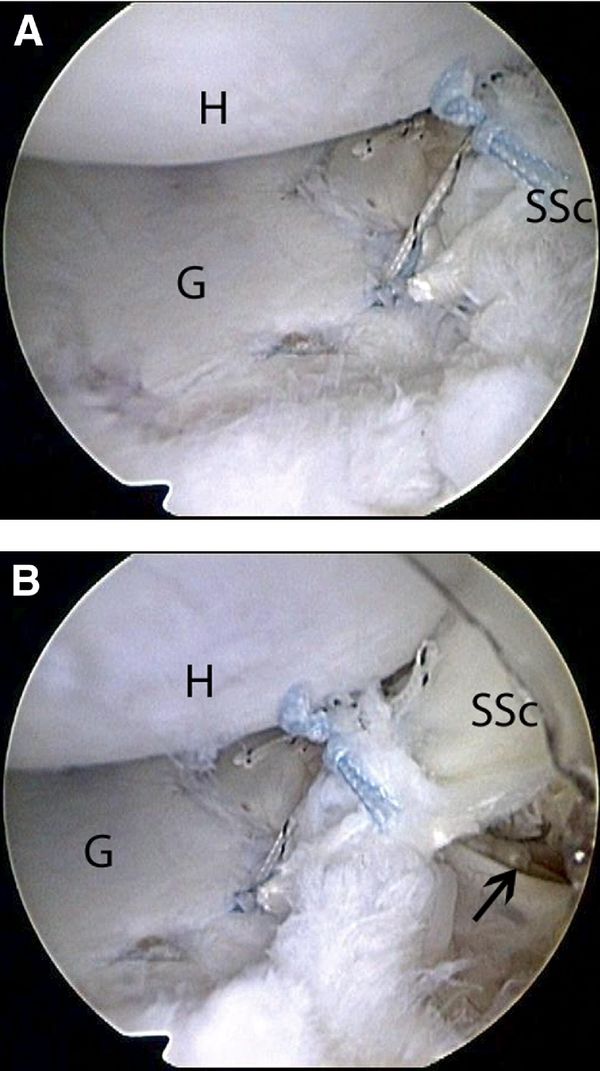

Dynamic anterior stabilization transfers the long head of the biceps to the anterior glenoid margin, thereby creating a “sling effect” (Figure).

The dynamic anterior stabilization technique provides decreased anterior glenohumeral translation in cases of Bankart lesions with limited anterior bone loss (<20%)[117]

In comparison with isolated Bankart repair it is able to stop the anterior translation less anterior and therefore reduces the risk of a conflict between the humeral head and the anterior margin of the glenoid. It is also easier and safer than arthroscopic Latarjet. Moreover, it does not require screws nor traction of the coracoid process, and should consequently reduce the risks of neurologic damage. Furthermore, the procedure can be performed with only 3 small incisions (Video), as it does not require coracoid transfer, which eliminates risks of nerve dissection, graft overhang and cortical resorption, hence reducing the probability for dislocation arthroplasty. Lastly, the pectoralis minor remains intact, which would avoid scapular dyskinesis. The potential drawbacks of the dynamic anterior stabilization are that it relies on the long head of biceps tendon, which has smaller diameter than the conjoint tendon, and could therefore have a weaker “sling effect” than that of the standard Latarjet. Also, there are, like in the Latarjet procedure, the risks of biceps pain, and secondary iatrogenic factors. Furthermore, in cases with larger bone defects (≥ 20 %) there is a relevant posterior and inferior shift of the humeral head in relation to the glenoid, when the arm is brought in the ABER position.(reference to be completed) Indications and limitations are yet to be defined and it is recommended that future studies are carried out with a more long-term follow-up.

Preoperative Patient Positioning

The operation, illustrated in the video, is performed in the semi-beach chair position under general anesthesia with an interscalene block. An examination under anesthesia is performed before prepping and draping the arm.

Initial Exposure and Portal Placement

An intra-articular approach is used through a standard posterior portal (soft spot), a standard diagnostic arthroscopy is performed with a 30-degree arthroscope and a pump maintaining pressure at 60 mm Hg. Antero-lateral and anterior portals are then established by an outside-in technique using a spinal needle as a guide. The rotator interval is opened, and the internal structures (glenoid defects, humeral defects, etc.) are further assessed with a probe.

Anterior Glenoid Preparation

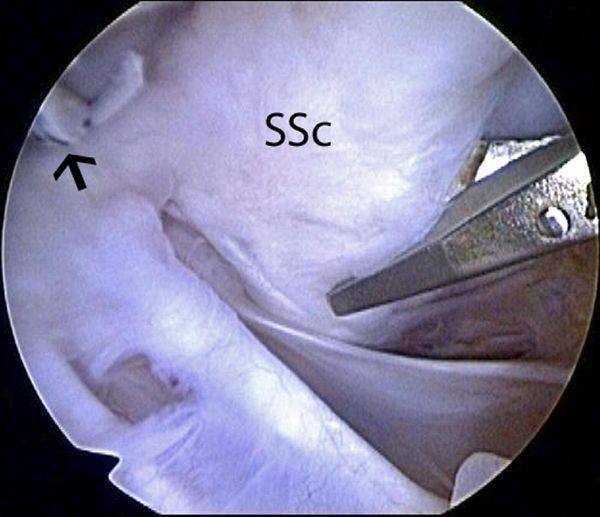

From a lateral viewing portal, the labrum, if necessary, is detached from the glenoid, and a suture is passed around the labrum and pulled through the posterior portal to increase access for preparation of the anterior glenoid (Figure). The glenoid neck is cleaned from soft tissues at around 3 o’clock with a burr.

Addressing the Long Head of Biceps and Subscapularis Split

The long head of biceps is then tenotomized and the biciptal groove is opened laterally and distally to avoid detaching the subscapularis (Figure).

The biceps is then exteriorized, and secured 20 mm from the proximal tendon. From a lateral viewing portal the subscapularis is exposed on three sides, together with the lateral margin of the conjoint tendon. Three options exist to create a split in the middle of the subscapularis above the junction of the superior two-thirds used in the standard Latarjet procedure: From a lateral viewing portal, either a switching stick (Wissinger Rod) can be passed across the glenohumeral joint through a posterior approach at the level of the inferior glenoid (Figure), an outside-in approach can be used or simply by passing through the subscapularis muscle with a suture passer, by grabbing the sutures that secure the biceps and pulling the biceps through the tendon.

The switching stick is now found in the retrocoracoid space and maintained lateral to the conjoint tendon to avoid damaging the nerve plexus. The probe is then introduced through the anterior portal to complete the split.

Long Head of Biceps Tenodesis to Anterior Glenoid

A drill is then used to prepare a hole at 3 o'clock from anterior to posterior within the neck of the glenoid, 2.0 cm deep, depending on the length of the interference screw. The LHB tendon is then passed through the subscapularis split into the pre-drilled hole, to establish the “sling effect”, and fixed using a tenodesis screw (Figure).

Labral Repair

With the arthroscope through the posterior portal, a standard Bankart repair is performed using 2-3 suture anchors. The anchors are placed on the glenoid rim at 3, 4, and 5 o’clock to enable the retention of the capsulo-ligamentous structures and to re-establish the labral damper effect (Video and Figure).

Postoperative Rehabilitation

Patients are instructed to wear a simple sling for 10 days encouraging rest and reducing the risk of post-operative hematoma formation. Rehabilitation with self-mobilization in elevation and external rotation is allowed from day 0. At 10 days, activities of daily living are allowed and self-mobilization in elevation and external rotation continued. Return to low-risk sports (eg, jogging, cycling, and swimming) is allowed at 6 weeks, and high-risk (throwing and collision) sports at 3 months only after satisfactory clinical and radiographic evaluations confirm satisfactory healing of the coracoid graft. Initially, no physiotherapy is recommended.

Bony procedures

In the setting of glenoid bone loss ≥20% of the glenoid diameter an arthroscopic Bankart repair has an unacceptably high rate of recurrence. Burkhart and DeBeer reported a 4% recurrence rate for arthroscopic Bankart repair when glenoid bone loss was <25%. However, with glenoid bone loss ≥25%, the recurrence rate was 67% with an arthroscopic approach. They subsequently recommended a bony procedure procedure in the population with substantial glenoid bone loss.[118]

Treatment is based on patient factors and associated pathology as previously discussed. In general, for patients under the age of 30, primary stabilization following a first traumatic anterior instability episode is offered. Such patients are counseled on the natural history or anterior instability and the potential for subsequent injury. For the majority of patients over the age of 30, nonoperative treatment is advised with standard sling immobilization for three weeks followed by progressive strengthening and return to activities. For such patients with persistent weakness or recurrent instability a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or MRI arthrogram is obtained to evaluate for an associated rotator cuff tear and stabilization is performed.

In consideration of the current literature, the following indications for osseous reconstruction procedures of the glenoid concavity can be recommended: - Substantial erosion-type defects (type IIIb), which constitute the instability-associated main pathology. - Chronic fragment-type defects (type II), where the glenoid area and concavity cannot be reconstructed by mobilization and refixation of the fragment. - In the rare patient with an acute, non-reconstructible, multifragmented glenoid fracture (type Ic). - In cases of revision surgery, e.g. after failed soft-tissue stabilization, a glenoid augmentation procedure is recommended also for smaller bony defects (type IIIa).

Latarjet

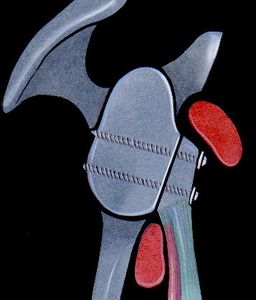

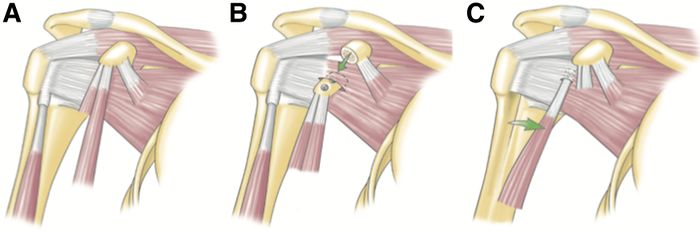

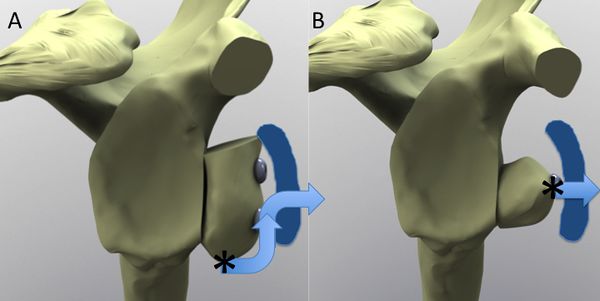

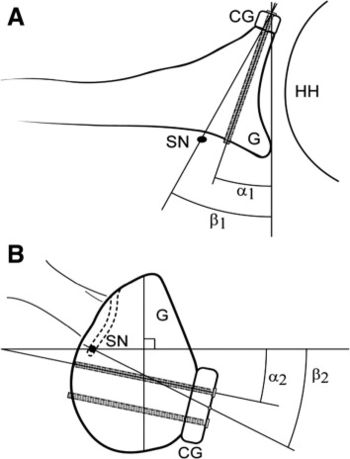

In 1954, Latarjet reported a coracoid transfer procedure in which the inferior aspect of the coracoid was secured to the anterior glenoid. The excellent stability of this procedure is obtained by a triple effect first proposed by Patte:[119]

1) the sling effect of the conjoint tendon when the arm is abducted and externally rotated, 2), the ‘‘bony effect’’ that increases or restore the glenoid anteroposterior diameter (Figure), and 3) the retensionning of inferior capsule to the stump of coracoacromial ligament, rending the coracoid extra-articular.

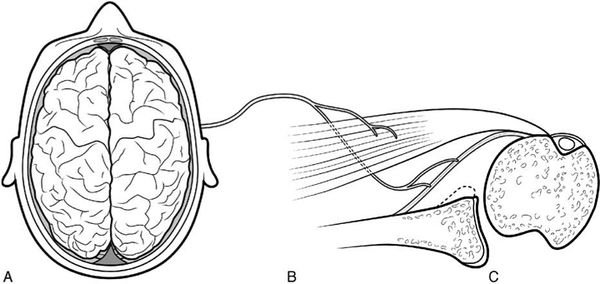

| A | B | C |

|---|

Figure. 28 Illustration of the three effects A) the sling effect, B) the bony effect and C) the retensioning of the capsule. Courtesy of Gilles Walch.

When the arm is at end-range position, the sling effect contributes 76-77% at different loads and the capsule the remaining 23-24% to the stabilization of the humeral head. At the mid-range position of the arm, the sling effect facilitates 51-62% and the bone block 38-49% of the stability. The sling effect therefore seems to constitute the number one stabilizing mechanism of the Latarjet procedure at both, the mid- and end-range of motion. The internal-external range of motion is thereby not significantly impaired.[120]

The Latarjet procedure is associated with a very low recurrence rate even in the setting of substantial glenoid bone loss and has become the gold standard of treatment in such settings. In addition, this non-anatomic method of anterior glenohumeral stabilization has progressively expanded and is actually the primary technique of choice for many European surgeons, as it prevents recurrent anterior instability in approximately 95 to 99% of cases. This procedure is also favored by some as a first choice in many contact athletes.[121]

Surgical technique (Video)

Patient preparation

The patient is positioned in a classical, 40 degrees, beach chair position, preferably under a combination of general anesthesia and locoregional interscalene block to maximize the patient and the surgeon’s comfort. A single prophylactic antibiotic dose is highly recommended, as infectious complications are not uncommon in the proximity of the axilla. The upper limb is draped freely to allow manipulation of the shoulder and placed on an arm board. The operative site, including the sternoclavicular joint medially, is covered with iodine incise drape.

Incision

The skin incision is vertical from the tip of the coracoid extending 4 to 5 cm toward the axillary fold. The trajectory should be slightly curved in order to avoid the axillary fold and thus the formation of postoperative adhesions.

Deltopectoral approach

The upper limb is laid on the armrest in slight abduction to release tension in the deltoid. The subcutaneous tissue is then dissected with a diathermy pencil and the deltopectoral grove, usually covered by a thin band of fat tissue, is looked for in its superior part. It is often challenging to locate in muscular patients and commonly found more medially. The grove is then dissected distally, with great care given to the cephalic vein and its branches that are a common source of bleeding, especially in the proximal part. An atraumatic autostatic valve retractor is placed, pulling back the deltoid laterally with the vein and the pectoralis major medially. The clavipectoral fascia is incised at the inferior border of the coracoacromial ligament and the lateral border of the coracobrachialis tendon, exposing the deep plane: coracoid process, coracoacromial ligament, pectoralis minor, coracobrachial and subscapularis tendons.

Coracoid preparation

While the arm is still abducted on the armrest, external rotation is applied in order to expose the coracoacromial ligament. Before taking any further step, preventive hemostasis of the acromial branch of the acromiothoracic artery that runs along the posterior part of the coracoacromial ligament must be realized. Only then can the ligament be safely removed, one centimeter from its coracoidal insertion. The patient’s arm is now placed in adduction and internal rotation and a pointed Hohmann is placed behind the coracoid elbow. The pectoralis minor tendon is visualized and totally detached from its bony insertion by electrocautery. The space between the coracobrachial tendon and pectoralis minor muscle is cautiously dissected with scissors, as the musculocutaneous nerve may emerge surprisingly high in this area. It is therefore wiser to first identify the nerve by palpation or direct visualization. Another danger is the presence of the underlying brachial plexus and axillary vessels, whose arising branches coursing in the surrounding adipose tissue may be a source of bleeding, and should thus be cauterized preventively. A 90 degrees oscillating saw is used to create a medial to lateral osteotomy. This typically allows for the harvesting of a 2.5 to 3 cm coracoid graft. The coracoid fragment is grasped with toothed (Museux) forceps. The oscillating saw is then used to decorticate the inferior coracoid surface. Two drill one cm apart holes are made using a 3.2 mm drill bit. The coracoid is then pushed beneath the pectoralis major until required later in the procedure.

Subscapularis tendon incision and capsulotomy

The subscapularis tendon is individualized and split horizontally (at the junction of the superior two-thirds and the inferior one-third or at its middle) (Figure).

A pointed Hohmann retractor is placed between the capsule and the subscapularis muscle in the subscapularis fossa. The split is maintained by a curved Gelpi. A 2 cm vertical incision in the capsule is made at the level of the joint line. The capsule is thereby incised on its vertical length, along the anterior border of the glenoid, and its lateral border is subsequently tagged with two sutures. A Trillat retractor is placed on the posterior glenoid rim, pushing back the humeral head. This maneuver can be aided by applying traction and internal rotation on the humerus. The glenohumeral articulation is henceforth well exposed, allowing proper assessment of the cartilaginous and labral integrity and removal of any intra-articular debris. A curved glenoid retractor is placed as medial as possible on the scapula neck.

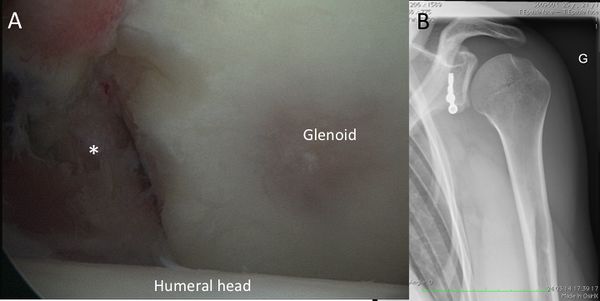

Glenoid preparation

At this stage, the anteroinferior quadrant of the glenoid should be perfectly exposed for preparation. The anterior glenoid surface is prepared with an osteotome to obtain a spongious bed for the graft.

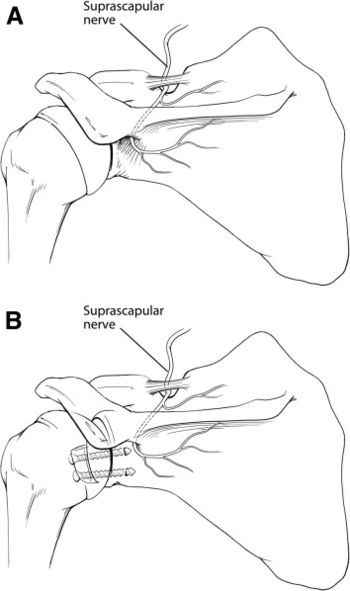

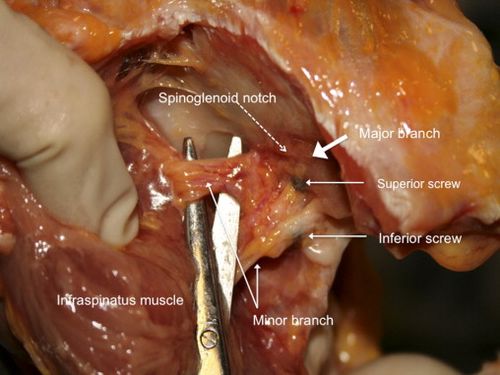

A 3.2 mm drill is used to first drill the inferior hole in the glenoid. The hole should be at the 5 o’clock position, 7 mm medially to the joint. When drilling, it is important to stay as parallel as possible to the glenoid surface, as an angle exceeding ten degrees in the axial plane puts the suprascapular nerve at high risk of lesion at its course on the posterior glenoid rim (Figure).[122]

Coracoid Positioning and Fixation

The coracoid bone block is now removed from its protective location behind the autostatic retractor. Usually, a 28-30 mm inferior screw is used. The graft is positioned on the prepared anteroinferior glenoid quadrant in such a way that its lateral border is perfectly flush with the glenoid. The superior hole is then drilled and measured with precision to avoid any screw protrusion. Another 4.5 mm self-tapping standard cortical screw is chosen accordingly. The capsule and the labrum are reinserted between the glenoid and the graft according to Luc Favard’s technique in order to decrease the risk of dislocation arthropathy (Video). The sutures are tighten with the arm positioned in full external rotation elbow at the side, elevation, with the assistant pushing the humeral head posteriorly in order to reduce the shoulder. Both screws are finally tightened using a ‘‘2-finger’’ technique.

Closure

The Trillat retractor is removed. The tendinous part of the subscapularis muscle lateral to the conjoint tendon is closed side to side with a non-resorbable suture, while making sure not to puncture the anterior ascending branch of the circumflex artery. The wound is closed and a drain is typically not used, unless excessive bleeding is noted.

Arthroscopic Latarjet

Surgical Technique

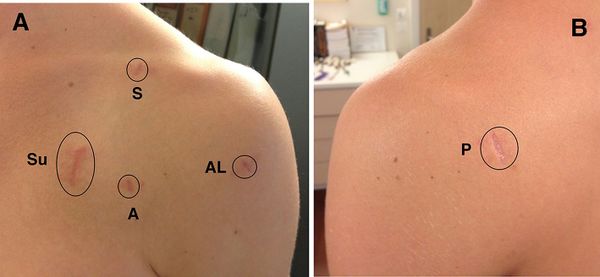

Operations are performed in the usual semi-beach chair position under general anaesthesia with an interscalenic block or catheter. Arthroscopic Latarjet are carried out using a total of 5 portals (posterior, anterolateral, anterior, suicide and superior to access the superior coracoid (Figure).

Intra-articular approach is carried out through the standard “soft spot” posterior portal. The rotator interval is opened, and the internal structures (glenoid defects, humeral defects, HAGL, etc.) are further assessed with the probe. To provide a healthy bed for graft healing, the glenoid neck is abraded between 2 and 5 o’clock with a burr. A release of the subscapularis on 270 degrees and of the lateral side of conjoint tendon are then performed. The two subscapularis nerves and the axillary nerve are only located and not dissected as this may lead to neurological lesions. From a lateral viewing portal, a switching stick is inserted through the posterior approach, passed across the glenohumeral joint at the level of the glenoid defect and then advanced through subscapularis to establish the level of split. From the suicide portal, a modified cannulated subscapularis splitter is advanced on the switching stick to facilitate the split.

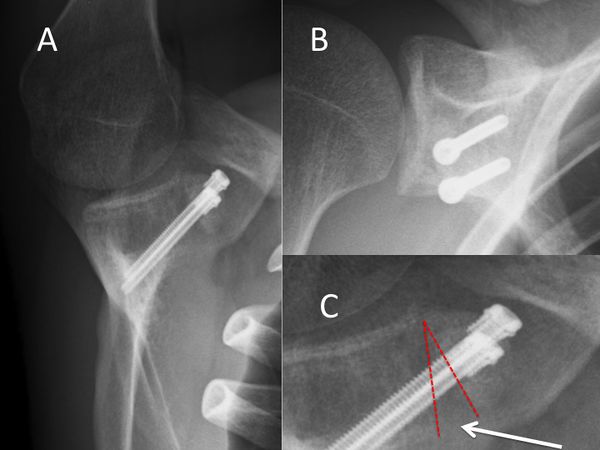

The probe is then introduced through the anterior portal to complete the split. The latter is thus done before coracoid osteotomy consequently protecting the plexus. At this point, with the scope in the anterior portal, the coracoid is prepared and then osteotomized with osteotome rather than a burr, in order to keep maximum graft length. The graft is extracted through the suicide portal and prepared outside, as inside debridement and trimming might be less accurate and puts the plexus at risk. The coracoid is then secured on the coracoid positioning cannula and positioned on the glenoid neck flush with the glenoid border. Two long K-wires are inserted through the coracoid positioning cannula, and the glenoid is drilled with a 3.2-mm drill bit. The length of the definitive screw is directly read from the depth gauge on the drill. The fixation is obtained with two 4.5-mm cannulated malleolar screws (Figure).

Bristow

Independently of Latarjet, Helfet reported in 1958 a slightly different procedure named after his master, Bristow, were the coracoid with conjoined tendon attached was pressed against the anterior glenoid by suturing it to a slit in the subscaplularis tendon instead of a screw.[123]

Despite the frequent synonymous labelling as “Bristow-Latarjet” coracoid transfer, the techniques remain distinct and non-equivalent reconstructive procedures. When differentiating between the coracoid transfer techniques, the stabilizing effect by the Bristow technique is inferior to that of the Latarjet procedure in cases of substantial glenoid bone loss due to the difference in coracoid graft size but also due to the direction of the conjoint tendon (Figure).[124]

Surgical technique

This subsection does not exist. You can ask for it to be created, but consider checking the search results below to see whether the topic is already covered

Arthroscopic Bristow (Video)

Coracoid Preparation, Drilling, and Osteotomy

The arthroscope is initially maintained in the posterior viewing portal. By use of electrocautery through the anterolateral portal, the rotator interval is opened and the subscapularis is followed medially to the coracoid. During this time, the arm should be internally rotated to relax the subscapularis. The coracoid is dissected and the coracoacromial ligament released. The anterior portal is established just medial to the coracoid, and the pectoralis minor is released. The undersurface of the coracoid is flattened with a motorized rasp through the anterolateral portal. The coracoid is drilled with a coracoid drill guide, a polydioxanone suture is passed through the bone tunnel, and the coracoid peg button is shuttled in place. Through the anterolateral portal, the coracoid undergoes osteotomy 1.5 to 2.0 cm from its tip.

Glenoid Preparation and Anchor Insertion

The labrum is released from the anterior glenoid neck, and a polydioxanone suture is placed through the labrum at the 5-o'clock position. The anterior glenoid neck is abraded to a flat surface using a motorized rasp and a suture anchor inserted at the 3-o'clock position to be used later for the Bankart repair.

Subscapularis Splitting and Axillary Nerve Protection

By use of switching sticks, the arthroscope is transferred to the northwest portal, the anterior glenoid neck preparation is confirmed, and a short half-pipe cannula is placed through the posterior portal. The glenoid drill guide is inserted over the cannula and placed flush with the glenoid face at the 5-o'clock position. A switching stick retracts the labrum and subscapularis through the west portal, and the glenoid tunnel is drilled from posterior with a 2.8-mm K-wire (the outer sleeve is left in place to facilitate the cortical-button transfer later). The posterior subscapularis spreader replaces the glenoid drill guide and is pushed through the subscapularis muscle along the 5-o'clock position, at the inferior one-third junction of the subscapularis. An anterior bursectomy is performed through the south portal to identify the “3 sisters” (anterior humeral circumflex vasculature), which are followed to the “2 brothers” (musculocutaneous and axillary nerves). The nerves are carefully protected with a nerve retractor, and the tip of the posterior spreader is slowly opened within the subscapularis muscle. The tendon is split from medial to lateral while the capsule is being preserved, and the anterior subscapularis spreader is inserted through the east portal with its tip medial to the posterior spreader.

Coracoid Transfer and Fixation

By use of a suture retriever through the posterior sleeve, the cortical button and coracoid bone block are transferred through the subscapularis muscle and lie flush with the anterior glenoid neck. This fixation is made using 2 round, 6.5-mm, slightly convex titanium buttons, connecting with a loop of continuous suture, forming 4 parallel strands. The glenoid cortical button is slid over the 4 white suture strands, a sliding-locking Nice knot is tied, and the button is advanced onto the posterior glenoid neck. A specific suture tensioner is used to increase bone compression to 100 N.

Bankart Repair

Using the previously placed glenoid anchor, we complete the labral repair, placing the bone block in an extra-articular position. Additional anchors can be inserted depending on the clinical situation and patient anatomy. The tensioning device is removed posteriorly, and 3 surgeon's knots are tied to complete the coracoid fixation.

Eden-Hybinette and Other Free Bone Block Transfers

Aiming to reduce donor site morbidity associated with the harvesting of autologous bone blocks, autografts of the iliac crest and distal clavicle and allograft of femoral head and distal tibia have been evaluated (Figure).[125][126][127][128]

Anatomically, iliac crest bone blocks offer the possibility of a nearly unrestricted graft size, but also the coracoid process was found to be a sufficient graft source to re-establish the anatomy for most glenoid defect cases.[129]

Provencher et al. described the use of an osteochondral tibia allograft with the advantages of a cartilaginous interface, improved graft availability and an excellent glenoid articular conformity.[130]

Radiologically, successful bony consolidation and a remodelling process of the allografts has been observed, as described for autologous glenoid reconstruction. However, a slightly higher recurrence rates of 0-22% were observed.

Surgical Technique

This subsection does not exist. You can ask for it to be created, but consider checking the search results below to see whether the topic is already covered.

Rehabilitation

Non-Operative Treatment of Acute First Traumatic Dislocations

Although positioning the arm in external rotation has been recommended, it has now clearly been demonstrated that immobilization of the shoulder in internal rotation after primary, traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation is sufficient.[131][132][133]

There is conflicting evidence regarding the length of immobilization required after dislocation but three weeks is typically recommended, followed by physical therapy for strengthening of the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers. Range of motion of the elbow, wrist, and hand are permitted immediately. Then, closed-chain exercises facilitate rotator cuff function to enhance joint stability and stimulate muscular coactivation and proprioception.[134]

For throwing athletes, a program is initiated and advanced, beginning at three months. A full return to sports is typically permitted at five to six months.

Rehabilitation Protocol After Bankart and Remplissage Stabilization

The shoulder is immobilized for four weeks using a sling. Passive and assisted-active exercises are then initiated for forward flexion and external rotation. After six weeks, patients begin strengthening exercises of the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers. For patients with a remplissage strengthening is delayed until twelve weeks postoperative. Patients are permitted to practice noncontact sports as soon as they recover their range of motion. Full return to throwing or contact sports is usually allowed after six months according to each individual’s functional recovery.

Rehabilitation Protocol After Dynamic Anterior Stabilization

Patients are instructed to wear a simple sling for 10 days encouraging rest and reducing the risk of post-operative hematoma formation. Rehabilitation with self-mobilization in elevation and external rotation is allowed from day 0. At 10 days, activities of daily living are allowed and self-mobilization in elevation and external rotation continued. Return to low-risk sports (eg, jogging, cycling, and swimming) is allowed at 6 weeks, and high-risk (throwing and collision) sports at 3 months. Initially, no physiotherapy is recommended.[135]

Rehabilitation Protocol After Latarjet Reconstruction

The shoulder is immobilized for ten days using a sling. The patient is asked to stretch in flexion and external rotation at least five times per day. No physical therapy is prescribed. The patient is not allowed to carry with his operated arm or to flex the elbow against resistance during the first six weeks. Activities of daily living are encouraged as comfort permits. At six weeks, non-contact sports are allowed. Return to contact sports is usually possible after three months assuming confirmation of bony union of the coracoid graft.

Results and Complications

Soft tissue procedures (Bankart, Remplissage)

Arthroscopic Bankart stabilization with use of suture anchors offers the advantage of being minimally invasive, allows assessment of associated pathology, and allows the surgeon to restores anatomy while reattaching the labral lesion and retensionning the glenohumeral ligament. While the short-term outcome of Bankart has been excellent, mid-term reported results show higher rates of recurrent of instability. According to the meta-analysis by Hobby et al., recurrence (dislocation and subluxation) after arthroscopic Bankart repair with suture anchors varies between 0 to 29.6%, with a mean of 8.9%.[136]

This rate of course varies with patient factors, particularly the amount of bony deficiency. Preoperatively, pitfalls are consequently to underestimate risk factors for recurrence for this surgery. In adolescent contact athletes undergoing arthroscopic labral repair, the overall recurrence rate is 51%. Rugby players who undergo primary arthroscopic shoulder stabilization aged <16 years have 2.2 times the risk of developing a further instability episode when compared with athletes aged ≥16 years at the time of index surgery, with a recurrence rate of 93%.[137]

Bankart repair combined with Malgaigne (Hill-Sachs) remplissage for large defects of the posterosuperior aspect of the humeral head may be an elegant approach in case of isolated humeral defect. Reported results are promising with a high rate of healing of the posterior aspect of the capsule and the infraspinatus tendon into the humeral defect, and a moderate loss of external rotation with the arm at the side. Moreover, most patients were able to return to sport including those involving overhead activities, around 70% at the same level.[138][139]

The Malgaigne remplissage is believed to be a posterior capsulotenodesis that acts as a checkrein diminishing anterior humeral head translation and reducing the risk of postoperative redislocation. However, some authors have observed that according to the location of the impaction fracture, the procedure actually corresponds to a capsulomyodesis including the teres minor muscle, rather than a capsolutenodesis as classically described (Figure).

Concerns about remplissage may include the potential muscle lesion to the external rotators, increased cost, and increased difficulty and operative time. Yet, beyond a slight loss in postoperative external rotation, there is no documented additional complication to remplissage.

Open Bone Block Procedures

Open anatomical bone grafting procedures show very good clinical mid- to long-term results. With this procedure return to sports activities is possible for at least 83% of patients regardless of the size of glenoid defect. In a study of 107 patients, Lädermann et al. reported a mean postoperative Walch-Duplay score of 93, good or excellent results in 97% of cases, and 95% of patients very satisfied or satisfied with their outcome.[140]

However, complications exist both in the short- and long-term. A systematic review of 30 studies with a total of 1658 coracoid transfers, also including more recent surgeries with shorter follow-up periods, reported a low recurrence rate of 6.0%. The arthropathy rates is also reduced to 17-36% compared to the original procedures. A systematic review of 30 studies, comprising a total of 1658 open coracoid transfers, recorded graft non-union or postoperative graft migration (10.1%), hardware complications (6.5%), instability (6.0%), graft osteolysis (1.6%), infection (1.5%), nerve palsy (1.2%), intraoperative fractures (1.1%) and hematoma (0.7%) with a revision surgery conducted in 4.9% of the cases. Hardware problems were identified as the most frequent reason for revision surgery. In addition to failure of stabilization, hardware or graft malpositioning and respective screw breakage, loosening or migration is attended with a high risk for soft tissue as well as articular surface damage.[141]

Regarding the postoperative muscle function, a significant strength deficit of the internal and external rotators was observed in comparison to the contralateral, unaffected shoulder.[142]

Risk of neurological impairment of the musculocutaneous nerve can be reduced by gently manipulating the coracoid process during preparation and avoiding an excessive medial dissection.[143]

The suprascapular nerve is at risk posteriorly during screw insertion and can be protected by parallel placement of the screws within 10 degrees of the glenoid surface in the axial plane (Figures).[144]

Arthroscopic Bone Block Procedures

Similarly, very good short-term results are achieved after arthroscopic glenoid rim reconstruction without events of postoperative redislocation and the advantage of subscapularis muscle preservation.[145][146]

At present, however, merely short-term results of the arthroscopic techniques are published and only by the pioneers of these techniques. Following the arthroscopic coracoid transfer techniques, recurrence rates of 0-2% were observed after short- to mid-term follow-up investigations.[147][148][149]

The arthroscopic approach is, however, quite challenging and requires a lengthy learning curve. When directly comparing the arthroscopic and open techniques, a similar functional outcome and patient satisfaction were achieved, but screw placement inaccuracy, persistent apprehension, recurrence rate and complications were higher for the arthroscopic approach.[150]

A slightly reduced percentage of graft non-union or postoperative graft migration (8.1%), hardware problems (2.3%), instability (1.7%) and nerve injury (0.6%) was recorded, while the rate of osteolysis (4.1%) increased. Conversion to an open approach had to be conducted in 3.5% of the surgeries. However, a smaller number of cases conducted by fewer surgeons is available for evaluation of the arthroscopic approach. Larger case numbers by different surgeons and long-term results are therefore required to validate these first positive outcomes.[151]

Remodeling of the Graft With Bone Block Procedure