Acute or Recurrent Anteroinferior Glenohumeral Instability

Contents

Bullet points

- One of most common shoulder injuries, 1.7% annual rate in general population.

- High recurrence rate that correlates with age at dislocation, up to 80-90% in teenagers (90% chance for recurrence in age <20).

- Osseous lesions, either humeral or glenoid, are identified in 95.0%. The risk of failure of arthroscopic treatment is higher if not addressed. A glenoid bony defect of >20-25% is considered "critical" and is biomechanically highly unstable and require bony procedure to restore bone loss (Latarjet, Bristow, other sources of autograft or allograft).

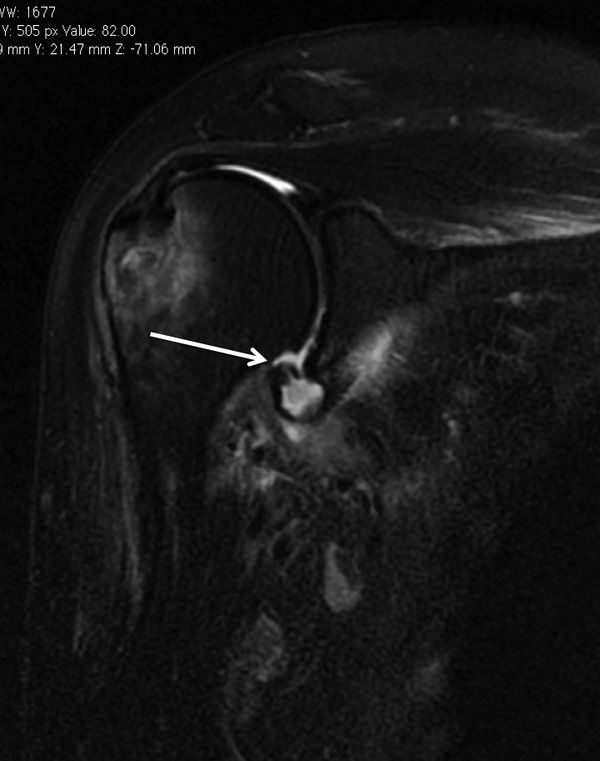

- A Malgaigne (Hill Sachs) defect is a chondral impaction injury in the posterosuperior humeral head secondary to contact with the glenoid rim. It is present in 80% of traumatic dislocations and 25% of traumatic subluxations.

- Axillary nerve injury is most often a transient neurapraxia of the axillary nerve and is present in up to 5% of patients.

- Incidence of associated rotator cuff tears increase with age of 40 (30% at 40, 80% at 60).

- Static glenohumeral stabilizers are the bone, the ligaments, the capsule, the labrum, and the negative pressure. The dynamic ones are the rotator cuff and long head of biceps tendon.

- The labrum contributes to 50% of additional glenoid depth.

- Anterior static shoulder stability with arm in 90 degrees of abduction and external rotation is provided by the anterior band of inferior glenohumeral ligament (main restraint).

- The middle glenohumeral ligament provides static restraint with arm in 45° of abduction and external rotation.

- The superior glenohumeral ligament provides static restraint with arm at the side.

- The physical examination demonstrates instability if the apprehension test is positive, multidirectional hyperlaxity when the external rotation at side is equal or above 85 degrees, and a pathological laxity of the inferior glenohumeral ligament if the hyperabduction test is positive.

- Three views plain radiographs, including true anteroposterior of the glenohumeral joint, scapular Y (scapular lateral), and Velpeau axillary views are the mainstay of imaging in the setting of acute traumatic anterior instability. Plain radiographs including anteroposterior in neutral, internal and external rotations, scapular Y and Bernageau views are obtained for recurrent instability. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) arthrogram is useful to assess for labral or rotator cuff tears, computed tomography (CT) for bone loss assessment.

- Conservative treatment after the first traumatic anterior dislocation is recommended for patients who are not actively engaged in sports, above the age of 30 years old, with a low functional demand, with an associated humeral fracture, or for the athlete with an in-season shoulder dislocation.

- Rehabilitation consist of strengthening of dynamic stabilizers (rotator cuff and periscapular musculature), exercises for proprioception and other specific treatments if apprehension persist.

- Surgical treatment included Bankart repair, capsular plication +/- soft tissue procedures (such as remplissage or dynamic anterior stabilization (DAS) if < 20% bone loss.

- If bone loss ≥ 20%, bone reconstruction with Latarjet, Bristow or free bone block transfers such as Eden-Hybinette is recommended.

Key words

Anterior glenohumeral instability; shoulder dislocation; subluxation; reduction; bone loss; Malgaigne; Hill-Sachs; Bankart; capsular shift; remplissage; dynamic anterior stabilization (DAS); Latarjet; Bristow; free bone block transfer; Eden-Hybinette; complication; recurrence; pull-out.

History

The first recorded depictions of shoulder reduction are ancient.[1]

Egyptian hieroglyphs dated 3000 years earlier, pictorially depict a leverage method of shoulder manipulation, They have been followed by the Greeks and Romans. Around 400 BC, Hippocrates, the father of Western medicine, introduced the traction method to reduce the shoulder. [2][3][4]

In 1855, Malgaigne was the first one to describe the humeral bone loss also called Hill-Sachs lesion.[5]

In the 1890s, the understanding of the unstable shoulder was elucidated by the work of two French researchers, Broca and Hartman who introduced the concept of capsulolabral damage following dislocations as possible cause of recurrent instability. Notably, most of the findings considered current hallmarks of shoulder instability, including Bankart lesion, bony Bankart, Kim lesion, as well as anterior and posterior labral periosteal sleeve avulsions and glenoid avulsions of glenohumeral ligaments, were described in their papers, decades before the eponymous figures to whom they are now commonly assigned depicted them.[6]

In 1906, Perthes in Germany and a few years later, Bankart in the UK ascertained that the detachment of the labrum caused instability of the shoulder and emphasized reattachment of the labrum to stabilize the joint.[7][8]

Current free bone grafting techniques are based on the initial descriptions by Eden in 1918 and Hybinette in 1932 using autologous iliac crest.[9][10]

Due to donor site morbidity with autologous iliac crest bone grafting techniques, different auto- and allogeneic bone materials have been evaluated as alternatives. Open and arthroscopic approaches using distal clavicle, femoral head, distal tibial allografts or coracoid process are currently used. The first coracoid process transplant was probably realized by the German surgeon Noeske in 1921.[11]

Nowadays, two most popular bony procedures included the Latarjet and its variant, the Bristow.[12][13]

Anecdote

(unpublished data, courtesy of Gilles Walch) At the beginning of the 1950s, Albert Trillat, the head of the orthopedic surgical clinic at the Edouard Herriot Hospital in Lyon (France) and also the promoter of the "no touch technique", reported combination of an anterior labro-ligamentous complex reinsertion when feasible with a reduction of a so-called coraco-glenoid outlet by means of a coracoid osteoclasy and nail fixation (Figures).[14]

Another surgeon, Michel Latarjet, who was mainly active in the field of thoracic surgery, visited Dr. Trillat to learn the aforementioned technique. When Latarjet supposedly tried to reproduce the Trillat procedure, he carried an involuntary complete coracoid osteotomy. Thenceforth, not knowing what to do with the bony fragment, he fixed it to the anterior glenoid through the subscapularis using a screw. From this mishap was born the operation which now bears his name.[15]

Anatomical Considerations

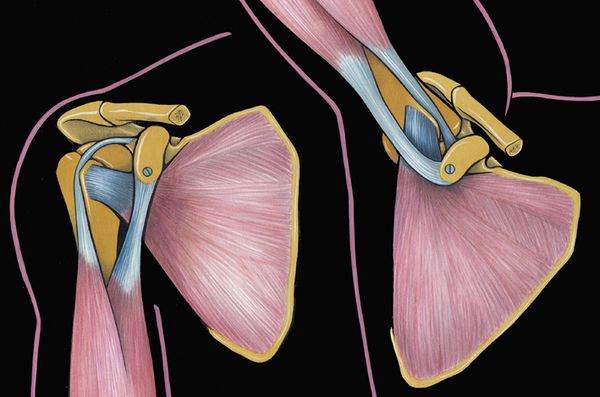

The glenohumeral joint has six degrees of freedom with minimal bony constraint that provides a large functional range of motion. It thus renders this diarthrodial joint particularly vulnerable to instability. The glenohumeral joint is stabilized by dynamic and static structures. The dynamic stabilizers include the rotator cuff, the long head of the biceps, and the deltoid. The static stabilizers of the joint include the capsule, the glenohumeral ligaments, the labrum, negative pressure within the joint capsule, and the bony congruity of the joint. The superior glenohumeral ligament functions primarily to resist inferior translation and external rotation of the humeral head in the adducted arm. The middle glenohumeral ligament functions primarily to resist external rotation from 0 degree to 90 degrees and provides anterior stability to the moderately abducted shoulder. The inferior glenohumeral ligament is composed of two bands, anterior and posterior, and the intervening capsule. The primary function of the anterior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament is to resist anteroinferior translation.[16]

Prevalence

The glenohumeral joint is the most commonly dislocated large joint of the body, affecting approximately 1.7% of the general population.[17]

In greater than 90% of cases, the instability is anterior, has a traumatic origin, and occurs in young athletes involved in contact sports.[18][19]

Ongoing sports participation in this population is associated with a high recurrence rate.[20]

Pathoanatomy and biomechanics

Anterior shoulder instability usually occurs with an anteriorly directed force applied to an abducted and externally rotated arm, or from a direct blow. During an anterior dislocation, many of the passive and active stabilizers may be damaged. The glenoid labrum, the glenohumeral ligaments, and the glenohumeral joint capsule, representing the soft tissue passive stabilizers will be injured; an avulsion of the anterior labrum, the classic Bankart lesion (Figure) or its variations (glenolabral articular disruption (GLAD), Perthes, anterior labroligamentous periosteal sleeve avulsion (ALPSA)) is almost invariably present,11,22,23 although it does not produce instability in isolation.[21][22][23][24]

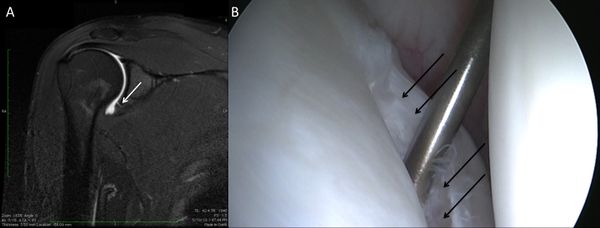

The anteroinferior glenohumeral ligaments and the capsule can be detached from the glenoid rim, and a plastic deformation of the glenohumeral ligaments or an HAGL lesion (Figure) are other common features.[25]

The plastic deformation of these structures becomes progressively more severe with subsequent episodes.[26][27][28]

The middle glenohumeral ligament functions to limit both anterior and posterior translation of the arm at 45 degrees of abduction and 45 degrees of external rotation whereas the inferior glenohumeral ligament resists translation of the arm in greater degrees of abduction.[29]

In addition to progressive soft tissue injury, recurrent dislocations can facilitate bony injury. Bony lesions are frequent in recurrent cases and may include defects of the glenoid (bony Bankart or beveling of the anterior glenoid resulting in loss of glenoid concavity), impaction of the posterolateral humeral head (Malgaigne lesion), or even coracoid or proximal humerus fractures (Figure).[30][31][32]

Given that the average glenoid diameter is about 24 mm, a 6 mm-wide or larger fragment of the glenoid will typically equate to a 25% or more of the articular surface and is considered a large bony fragment.[33][34]

Such significant glenoid bone loss can be viewed arthroscopically as an inverted pear configuration. All Malgaigne lesions are by definition engaging lesions (since it has engaged at least once). Thus, the notion of “engaging” versus “non-engaging” can lead to significant confusion. Some have proposed that the important lesions are those that engage in the 90-90 position.

Finally, the active restraint, mainly a lesion of the rotator cuff above the age of 40, will complete this complex situation.[35][36]

The glenohumeral joint is stabilized by a so-called “concavity compression” principle with the rotator cuff pulling the humeral head into the glenoid concavity and therefore ensuring stability through counteracting decentering translational forces.[37][38][39]

Natural History and Risk Factors of Dislocation or Recurrences

To understand the natural history of instability and its importance for the appropriate management of this pathology, the following questions should be answered: What happens in the shoulder after the first dislocation? Which structures suffer damage? Who are the patients at higher risk of recurrence? How does the disease evolve without treatment? Will surgical treatment avoid future negative outcomes and prevent degenerative joint disease? Who should we treat and when?[40]

80% of anterior-inferior dislocations occur in young patients. Recurrent instability is common and multiple dislocations are the rule. Instability is influenced by a large number of variables, including age of onset, activity profile, number of episodes,delay between first episode and surgical treatment. The different risks factors are:

-Young males, (up to 100% of recurrence)[41][42]

-Practice of contact sports, forced overhead activity,

-Sport practice at a competitive level,[43]

-Bony impairment,

-Concomitant hyperlaxity.[44]

Natural History

Classification

Instability can be classified as primary or recurrent. The latter can be further classified as dislocation, subluxation, apprehension, or an unstable painful shoulder. In frank dislocation, the articular surfaced of the joint are completely separated. Subluxation is defined as symptomatic translation of the humeral head on the glenoid without complete separation of the articular surfaces. Apprehension is classically defined by fear of imminent dislocation in the 90-90 position. This could correspond to an instability phenomena or a persistent fear after a successful glenohumeral stabilization (please refer to Apprehension chapter).

45. Haller S, Cunningham G, Lädermann A, et al. Shoulder apprehension impacts large-scale functional brain networks. AJNR American journal of neuroradiology 2014;35:691-7.

The unstable painful shoulder presents as pain only (as opposed to a sense of instability) during an apprehension maneuver at clinical examination.

46. Boileau P, Zumstein M, Balg F, Penington S, Bicknell RT. The unstable painful shoulder (UPS) as a cause of pain from unrecognized anteroinferior instability in the young athlete. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2011;20:98-106.

47. Patte D, Bernageau J, Rodineau J, Gardes JC. [Unstable painful shoulders (author's transl)]. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot 1980;66:157-65.

The majority of these patients has a history of trauma, but simply do not report a clear history of trauma. Careful preoperative and/or arthroscopic examination will show that the majority of these patients also have evidence of instability (i.e. labral tear, glenoid fracture, or Malgaigne (Hill-Sachs) lesion)

Five types of traumatic anterior dislocation have been described. The subcoracoid dislocation has an antero-inferior direction and is the most common. Other types, including subglenoid, subclavicular, retroperitoneal, and intrathoracic are rare and usually associated with severe trauma.

48. Patel MR, Pardee ML, Singerman RC. Intrathoracic Dislocation of the Head of the Humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1963;45:1712-4.

49. Wirth MA, Jensen KL, Agarwal A, Curtis RJ, Rockwood CA, Jr. Fracture-dislocation of the proximal part of the humerus with retroperitoneal displacement of the humeral head. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1997;79:763-6.

Osseous defects of the anterior glenoid rim can be classified into three types according to their pathomorphology. In particular, acute (type I) and chronic glenoid rim defects (type II and III) are differentiated, which are provoked either by an acute glenoid fracture or recurrent shoulder dislocations with subsequent erosion of the glenoid rim. Type I lesions are further divided into bony Bankart lesions (type Ia), solitary glenoid rim fractures (type Ib) and multifragmented glenoid rim fractures (type Ic). In most cases, type I glenoid defects can sufficiently be reconstructed by mobilization and anatomical refixation of the fragment. In cases of complex multifragmented glenoid rim fractures (type Ic), however, it may be necessary to resect the fragments and augment the glenoid defect. Type II defects include chronic fragment-type of lesions that are characterized by an extra-anatomically consolidated or pseudarthrotic fragment of insufficient dimensions for a defect reconstruction due to resorption processes. A bony glenoid augmentation may be indicated, depending on the dimensions of the glenoid defect and the remaining fragment. Erosion-type of defects (type III) are predominantly observed in patients with recurrent anterior shoulder dislocations. These usually develop on the basis of a glenoid fracture with subsequent resorption of the fragment, or as a result of chronic abrasion of the anterior glenoid rim. If the bone loss adopts substantial dimensions, mere soft-tissue stabilization procedures are not sufficient in re-establishing stability.

Clinical Presentation and Essential Physical Examination

The history should document age, hand dominance, occupation, participation in sporting activities, initial mechanism of the injury, the position of the arm (extension, abduction, and external rotation favors anterior dislocation), how long the shoulder stays out, the method of reduction, the number of recurrences (frank dislocation vs subluxation), and the effectiveness of a previous nonoperative or operative treatment. The diagnosis of recurrent traumatic anterior glenohumeral instability is usually made easily on the basis of the history, radiographs, and a positive apprehension sign. However, when collision athletes are seen, care should be taken because they may not experience clear dislocation or subluxation and only complain of pain or weakness.

A comprehensive physical examination is essential. The aim is to define the direction of instability, the presence of an associated pathologic hyperlaxity, and to exclude neurological and rotator cuff impairment. Passive and active glenohumeral range of motion should be assessed. Rotator cuff examination includes strength tests such as belly-press, bear hug, Jobe tests and strength in external rotation again resistance (please refer to Rotator Cuff Pathology/Rotator cuff complete lesion). Tests for anterior and superior labral lesions are not systematically perform as they have a poor sensitivity and specificity.

50. Cook C, Beaty S, Kissenberth MJ, Siffri P, Pill SG, Hawkins RJ. Diagnostic accuracy of five orthopedic clinical tests for diagnosis of superior labrum anterior posterior (SLAP) lesions. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2012;21:13-22.

The neurovascular status of the upper extremity is assessed, particularly with regard to the axillary nerve since there is a high incidence of injury to this nerve with traumatic instability (Figure).

References

- ↑ Iqbal S, Jacobs U, Akhtar A, Macfarlane RJ, Waseem M. A history of shoulder surgery. Open Orthop J 2013;7:305-9.

- ↑ Hussein MK. Kocher's method is 3,000 years old. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1968;50:669-71.

- ↑ Celsus A. De Medicina.

- ↑ Hippocrates. Corpus Hippocraticum—De articulis.

- ↑ Malgaigne J. Traité des fractures et des luxations. Paris: J.-B. Baillière; 1855.

- ↑ Broca A, Hartmann H. Contribution à l'étude des luxations de l'épaule (luxations anciennes et luxations récidivantes). Bull Soc Anat 1890;4:416-23.

- ↑ Perthes G. Ueber Operationen beihabitueller Schulterluxation. Dtsch Z Chir 1906;85:199–227.

- ↑ Bankart AS. Recurrent or Habitual Dislocation of the Shoulder-Joint. British medical journal 1923;2:1132-3.

- ↑ Eden R. Zur Operation der habituellen Schulterluxation unter Mitteilung eines neuen Verfahrens bei Abriss am inneren Pfannenrande. Dsch Z Chir 1918;144:269.

- ↑ Hybinette S. De la transplantation d’un fragment osseux pour remédier aux luxations récidivantes de l’épaule. Acta Chir Scand 1932:411-45.

- ↑ Anonymous. Zentralbl Chir 1924;43:2402.

- ↑ Latarjet M. Treatment of recurrent dislocation of the shoulder. Lyon Chir 1954;49:994-7.

- ↑ Helfet AJ. Coracoid transplantation for recurring dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1958;40-B:198-202.

- ↑ Trillat A. Traitement de la luxation récidivante de l'épaule. Considérations techniques. Lyon Chir 1954:986-93.

- ↑ Latarjet M. Treatment of recurrent dislocation of the shoulder. Lyon Chir 1954;49:994-7.

- ↑ Burkart AC, Debski RE. Anatomy and function of the glenohumeral ligaments in anterior shoulder instability. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2002:32-9.

- ↑ Romeo AA, Cohen BS, Carreira DS. Traumatic anterior shoulder instability. Orthop Clin North Am 2001;32:399-409.

- ↑ Goss TP. Anterior glenohumeral instability. Orthopedics 1988;11:87-95.

- ↑ Owens BD, Agel J, Mountcastle SB, Cameron KL, Nelson BJ. Incidence of glenohumeral instability in collegiate athletics. Am J Sports Med 2009;37:1750-4.

- ↑ Owens BD, Dickens JF, Kilcoyne KG, Rue JP. Management of mid-season traumatic anterior shoulder instability in athletes. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2012;20:518-26.

- ↑ Bankart AS. Recurrent or Habitual Dislocation of the Shoulder-Joint. British medical journal 1923;2:1132-3.

- ↑ Neviaser TJ. The anterior labroligamentous periosteal sleeve avulsion lesion: a cause of anterior instability of the shoulder. Arthroscopy 1993;9:17-21.

- ↑ Neviaser TJ. The GLAD lesion: another cause of anterior shoulder pain. Arthroscopy 1993;9:22-3.

- ↑ Speer KP, Deng X, Borrero S, Torzilli PA, Altchek DA, Warren RF. Biomechanical evaluation of a simulated Bankart lesion. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1994;76:1819-26.

- ↑ Wolf EM, Cheng JC, Dickson K. Humeral avulsion of glenohumeral ligaments as a cause of anterior shoulder instability. Arthroscopy 1995;11:600-7.

- ↑ Bigliani LU, Pollock RG, Soslowsky LJ, Flatow EL, Pawluk RJ, Mow VC. Tensile properties of the inferior glenohumeral ligament. J Orthop Res 1992;10:187-97.

- ↑ Habermeyer P, Gleyze P, Rickert M. Evolution of lesions of the labrum-ligament complex in posttraumatic anterior shoulder instability: a prospective study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1999;8:66-74.

- ↑ Urayama M, Itoi E, Sashi R, Minagawa H, Sato K. Capsular elongation in shoulders with recurrent anterior dislocation. Quantitative assessment with magnetic resonance arthrography. Am J Sports Med 2003;31:64-7.

- ↑ Burkart AC, Debski RE. Anatomy and function of the glenohumeral ligaments in anterior shoulder instability. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2002:32-9.

- ↑ Griffith JF, Antonio GE, Yung PS, et al. Prevalence, pattern, and spectrum of glenoid bone loss in anterior shoulder dislocation: CT analysis of 218 patients. AJR American journal of roentgenology 2008;190:1247-54.

- ↑ Buscayret F, Edwards TB, Szabo I, Adeleine P, Coudane H, Walch G. Glenohumeral arthrosis in anterior instability before and after surgical treatment: incidence and contributing factors. Am J Sports Med 2004;32:1165-72.

- ↑ Edwards TB, Boulahia A, Walch G. Radiographic analysis of bone defects in chronic anterior shoulder instability. Arthroscopy 2003;19:732-9.

- ↑ Burkhart SS, De Beer JF. Traumatic glenohumeral bone defects and their relationship to failure of arthroscopic Bankart repairs: significance of the inverted-pear glenoid and the humeral engaging Hill-Sachs lesion. Arthroscopy 2000;16:677-94.

- ↑ Burkhart SS, Debeer JF, Tehrany AM, Parten PM. Quantifying glenoid bone loss arthroscopically in shoulder instability. Arthroscopy 2002;18:488-91.

- ↑ Antonio GE, Griffith JF, Yu AB, Yung PS, Chan KM, Ahuja AT. First-time shoulder dislocation: High prevalence of labral injury and age-related differences revealed by MR arthrography. JMRI 2007;26:983-91.

- ↑ Itoi E, Tabata S. Rotator cuff tears in anterior dislocation of the shoulder. Int orthop 1992;16:240-4.

- ↑ Lazarus MD, Sidles JA, Harryman DT, 2nd, Matsen FA, 3rd. Effect of a chondral-labral defect on glenoid concavity and glenohumeral stability. A cadaveric model. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996;78:94-102.

- ↑ Matsen FA, 3rd, Harryman DT, 2nd, Sidles JA. Mechanics of glenohumeral instability. Clinics in sports medicine 1991;10:783-8.

- ↑ Yamamoto A, Takagishi K, Osawa T, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of a rotator cuff tear in the general population. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2010;19:116-20.

- ↑ Carpinteiro EP, Barros AA. Natural History of Anterior Shoulder Instability. Open Orthop J. 2017 Aug 31;11:909-918.

- ↑ Postacchini F, Gumina S, Cinotti G. Anterior shoulder dislocation in adolescents. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2000;9:470-4.

- ↑ Hovelius L, Augustini BG, Fredin H, Johansson O, Norlin R, Thorling J. Primary anterior dislocation of the shoulder in young patients. A ten-year prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996;78:1677-84.

- ↑ Balg F, Boileau P. The instability severity index score. A simple pre-operative score to select patients for arthroscopic or open shoulder stabilisation. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2007;89:1470-7.

- ↑ Habermeyer P, Jung D, Ebert T. [Treatment strategy in first traumatic anterior dislocation of the shoulder. Plea for a multi-stage concept of preventive initial management]. Der Unfallchirurg 1998;101:328-41.