Posterosuperior Rotator Cuff Tears and Associated Pathologies

Contents

- 1 Bullet Points

- 2 Key Words

- 3 What would Codman have thought about this?

- 4 Biomechanics of the Posterosuperior Rotator Cuff

- 5 Clinical examination

- 6 Imaging

- 7 Classification

- 7.1 Type A: Bony Involvement

- 7.2 A.3 Tuberosity Insufficiency

- 7.3 Surgical Technique

- 7.4 Type B: Full Thickness Tendon Lesion

- 7.4.1 B1: Lateral tendinous disruption

- 7.4.1.1 Size of Tendon Lesion

- 7.4.1.2 Tendon Retraction

- 7.4.1.3 Tear Pattern

- 7.4.1.4 Releases for the Rotator Cuff

- 7.4.1.5 Double-Row Versus Single-Row Cuff Repair

- 7.4.1.6 Margin Convergence

- 7.4.1.7 Load Sharing Rip Stop Construct

- 7.4.1.8 Massive Posterosuperior Rotator Cuff Tears

- 7.4.1.9 Definition and Classification of Massive Rotator Cuff Tears

- 7.4.1.10 Suprascapular Nerve Neuropathy and Massive Rotator Cuff Tear

- 7.4.2 Treatment Options for Massive Rotator Cuffs

- 7.4.3 B2: Medial Tendinous Disruption

- 7.4.1 B1: Lateral tendinous disruption

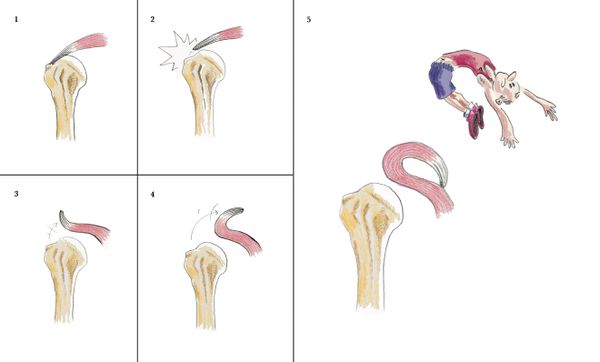

- 7.5 B3: Tendon to Tendon Adhesion: “Fosbury Flop Tear”

- 7.6 Type C: Musculotendinous Junction Lesion

- 7.7 Type D: Muscle Insufficiency

- 8 Irreparable Rotator Cuff Tears

- 9 References

Bullet Points

- The rotator cable explains why patients with most rotator cuff tears can maintain active forward flexion, and also why even after only a partial rotator cuff repair, good functional results can be achieved.

- The most important negative prognostic factor is high-grade fatty infiltration of the rotator cuff muscle bellies (grade 3 or 4 fatty infiltration).

- The tangent sign is an indicator of advanced fatty infiltration and is a predictor of whether a rotator cuff tear will be reparable.

- Full thickness disruption of the lateral tendon stump (B1) is the most frequent type of rotator cuff lesion, comprising approximately 90% of all surgically treated lesions.

- Musculotendinous junction lesions (C-type) or rare and characterized by an edema of the muscle belly. They are associated to calcific deposit (infraspinatus) or trauma (supraspinatus). Unrepaired, grade III lesions lead rapidly to grade 4 fatty infiltration of the muscle.

- Tendon retraction is classified according to Patte. Overreduction and lateral transposition of the tendon over the greater tuberosity may be unphysiological.

- Massive rotator cuff has different definitions in the literature, each having potential benefits or drawbacks.

- Massive rotator cuff tears comprise approximately 20% of all cuff tears and 80% of recurrent tears.

- The classification of Collin not only subclassifies massive tears but has also been linked to function, particularly the maintenance of active elevation.

- Non-surgical treatment is effective in patient with massive rotator cuff if the tear involves less than three tendons and do not involves the subscapularis (D-type).

- Biomechanical testing has consistently demonstrated the superiority of double-row constructs over single-row. However, there is no obvious difference clinically.

- There is actually no support for routine suprascapular nerve release when massive rotator cuff repair is performed.

- Functional outcome improved after revision rotator cuff repair and 70% or more of patients were satisfied or very satisfied. However, the prevalence of persistent defect (retear or non-healing) is 28% at six months and 40% at two years.

- Rotator cuff are irreparable when associated to true pseudoparalysis with the presence of lag signs (external rotation lag, drop, dropping, hornblower signs), femoralization of the humerus or acetabulization of the acromion, grade 3 or 4 fatty infiltration and tangent sign.

- The current literature does not support the initial use of complex and expensive techniques in the management of posterosuperior irreparable rotator cuff tears.

Key Words

Shoulder arthroscopy; Rotator cuff lesion; Partial repair; Tear pattern; Classification; Massive; Reparable and non-repairable; Irreparable; Imaging; Recurrent; Failed; Revision surgery; Open and arthroscopic approach; Conservative or non-operative treatment; Physiotherapy; Functional outcomes; Prognostic factors; Latissimus dorsi transfer; Subacromial spacer interposition; Balloon; Biceps tenotomy; Superior capsular reconstruction; Reverse arthroplasty; Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) arthrography (MRA); Fosbury flop tear; New tear pattern; FUSSI; SAM.

What would Codman have thought about this?

OPERATIVE TREATMENT OF RUPTURE OF THE SUPRASPINATUS TENDON

The best time to operate would be immediately after the injury. When in doubt of the diagnosis, exploratory incision of the bursa should be done. The technique of this incision is the same as that which has just been described for use in cases of calcified deposits. Practically the whole base of the bursa can be inspected through this incision and the exact extent of the rupture determined. The incision is then enlarged inward or outward at either end for a half-inch, depending on the direction of the tear. On account of the herringbone structure of the deltoid it makes little difference whether or not the enlargement of the incision is at an angle with the first one. A good exposure can be obtained with an incision one and one- half to two inches in length. Do not enlarge upward farther than the coraco-acromial ligament. Assuming that the operation is done soon after the accident, it would seem that no special directions would be needed. The surgeon knowing the normal relations would restore them by appropriate sutures and close the wound in his favorite manner. It seems to me that this immediate operation would be very easy, but I have not been able to operate on one of these cases in an early stage. In general the operation has two main objects: the repair of the tendon to give power to the arm, and the making of a frictionless lower bursal surface to relieve inflammation and pain. Perhaps the latter is more important, for even a powerful arm, if painful, is not as useful as an arm which is rather weak in the power of abduction but not painful. It is important to keep these two objects in mind, for although in some cases both can be attained, it is sometimes necessary to take a choice between them, because the tissues may be so damaged and retracted that good approximation is impossible. In such a case we may wish to discard all hope of restoring power and devote our whole effort to trying to allay friction. For instance, the tuberosity could be excised wherever it is free from tendinous attachment, and hence is useless. This might diminish the pain by removing the eminence. One must not feel too discouraged, however, about his repair work, for on several occasions I have opened a bursa a second time and found a smooth base and no visible sign of my suture, which, at the end of my previous operation, had appeared rough and clumsy with the ends of the tendons not even approximated but held "a distance." (See p. 245.) Even in a certain number of the delayed cases which I have operated upon, there has been little difficulty in making a satisfactory suture aiming for both objectives, but in other cases, there was little or no hope of making a smooth, even suture which would leave no rough eminence or sulcus. The latter is particularly likely to be the case where the tendon is evulsed from the tuberosity, leaving no stub to hold the stitches. In a few cases the retraction was so great that no suture could be attempted at all.

Special Points and Special Difficulties

I have found that in the old cases on which I have operated, it is seldom easy, often difficult and sometimes impossible to repair the tendon. It seems best to list the difficulties and then to discuss each.

Position on table Mobilizing the tendons The long head of the biceps. Drilling the tuberosity or removing it. Suturing the rent. Formation of a new sulcus. Frictionless surface Material of suture.

Shape of needles.

Closure of bursa. Disposal of fluid. Postoperative treatment.

1. The arrangement of the position of the patient on the table to permit proper mobilization of the arm during the operation, is an important factor in technique. The point of the shouldeT is a difficult region on which to work, for both the surgeon and the assistants. It slinks away and the patient's head and neck seem to wish to take its place. (See Fig. 50.) I should like to stress the importance of so placing a heavy sand bag under the shoulder and another under the corresponding hip that the patient is half turned on his side, while the head, with the face turned away, is at a lower level than the point of the shoulder. The shoulder should be slightly over the edge of the table toward the operator, so that the arm may be allowed to hang down in a position of dorsal flexion when desired. This position throws the distal portion of the supraspinatus tendon forward for the maximum distance from under the acromion.

The operator and assistant stand on the same side of the table, while the anaesthetist and nurse with the instrument table are on the other side. A second assistant is welcome, and often almost necessary, because the first assistant must at times give his entire attention to holding the arm and the nurse may be occupied with retractors. Much of the facility with which the operation is conducted depends on the assistant who holds the arm, for his ability to rotate just at the right time will enable the operator to put his needle at just the right point in the somewhat small field. Since the lips of the incision do not move appreciably, the operative field is really controlled by the assistant as he rotates the humerus, bringing this side of the rent or that into a position which the operator desires. The maneuver already described, of letting air into the joint and bursa, is often a great help. The position in which to place the sutures is best illustrated by a diagram. (Fig. 52.) While this is the ideal, it is seldom possible to carry it out exactly, for too often the retracted, stiffened tissues cannot be worked into nice apposition.

FIGURE 52. METHODS OF PLACING SUTURES a illustrates the writer's suggestion that the biceps tendon may be sutured to the supraspinatus in some cases when the former has been already torn from the edge of the glenoid, b, c, and d suggest the method of placing the sutures in the ruptured supraspinatus and in the tuberosity. The ideal is c, for in this case the lines of incision have been carried up on each side of the supraspinatus to mobilize it. d illustrates Dr. Wilson's method of cutting a slot to receive the supraspinatus tendon, e and / offer a suggestion for operation in a case where the short rotators have been entirely evulsed from the head of the humerus. Fascia lata might be passed through a drill hole and through a slot over the tuberosity to form an anchorage for the tendons.

2. Mobilizing the tendons. When one considers that each one of the short rotators is separated from the other by a definite bony partition through most of its extent, and it is only the last three-quarter inch which is welded with the others into the terminal conjoined tendon or cuff (Fig. 10), it would seem easy to isolate any one tendon so that the more or less elastic muscle belly could be stretched enough to bring the tendon down again to the tuberosity and suture it there. However, if you try this on a normal shoulder at autopsy, you will find it is not easy, and when you try it on a ruptured tendon in which operation has been delayed for many months, you will find it impossible. In the first place, you are cramped for room by the acromion and coraco-acromial ligament so that you cannot see the muscle bellies even in the normal shoulder. In the second place, if you dissect back more than an inch on either the supraspinatus or infraspinatus, you run the risk of wounding the suprascapular nerve, and if you do, you may lose your power in those muscles forever. In order to get at these tendons more effectively, I used to use the "sabre-cut incision," which gave a perfect exposure and every possible opportunity. (Plate VIII.) Even then the mobilization was only a little more satisfactory, so I have given up this incision. Practice has given me a little more confidence, and I believe now I can do almost as well through the simple routine incision. Dr. William Rogers has suggested removing the deltoid attachment with the periosteum from the acromion and suturing them back at the end of the operation." This seems rational, but I have not tried it and do not know whether one may rely on having the deltoid origin anchor again satisfactorily. I have sometimes thought that a subcutaneous osteotomy of the base of the acromion might mobilize it enough even without division of the coraco-acromial and acromioclavicular ligaments to allow easy access. The trouble with any incision which mobilizes the acromion is the long period which one must wait for union to occur before moving the joint. I am inclined at present to do all the mobilizing I can through the routine incision, and I find that I am constantly improving in my ability to do this. It is probably best to remove the falciform edge of new tissue and to refresh the edges of the tendon itself. I attribute some of my imperfect results to my failure to do this. One learns by experience to put the suture back of the falciform edge, for the latter has no strength and the stitch at once tears out. One is tempted not to remove the edge because it is obviously difficult to close the rent without using it, and it seems folly not to save all the tissue one can. It might be contended that the falciform edge may have more tendency to unite than the real tendon substance, which has very little blood supply, so that perhaps I may be wrong in recommending the removal of this new tissue with which nature is attempting to repair the damage. The method of closure which seems to me the best is illustrated in Fig. 52.

3. The long head of the biceps. The problems connected with how to deal with the long head of the biceps when it is found exposed, owing to the retraction of the ruptured tendons, are not a few. I can only discuss them and do not pretend to solve them. Although I am not in agreement with some of Meyers' views on the importance of the role of the biceps tendon in shoulder injuries, I feel that his observations ought to be known to every one who operates on these cases. To my mind, the rupture of the supraspinatus is the primary and important lesion which uncovers the biceps tendon, makes it slip a little at the top of the bicipital groove and to tend to be caught between the tuberosity and the acromion. At any rate, one often finds it a conspicuous, pink, inflamed-looking, swollen band lying across the j oint cartilage at the bottom of the rent. ( Plate VIII.) The portions exposed in the rent look inflamed; those covered by the remaining intact part of the capsule are white, glistening and normal. It is pretty obvious that our suture should cover up the biceps tendon without interfering with it otherwise. It usually lies just under the inner edge of the rent, but if any of the subscapularis fibers are involved, it lies entirely exposed. Sometimes it is not found at all, for it has been torn away from its glenoid attachment and has retracted down the bicipital groove. Sometimes it is split in two, longitudinally. Often it is flattened and frayed at the edges. Varying proportions of it may be ruptured. It may be composed of indefinitely separated longitudinal strands, some of which have become welded into the capsule. It may have little, rice-like tags on its edge. However, almost always the parts which do not become exposed in the gap left by the supraspinatus are normal in appearance. When it has ruptured from the glenoid, it may be held high in the groove by a few remaining bands, and we can capture it and pull it up. What shall we do with it? We might try to suture it back on the glenoid, or rather on the fibrocartilage which surrounds the glenoid. Or we might attach it to the proximal portion of the supraspinatus, or to the capsule, or anchor it in the groove, or excise a part of it and use it to repair the supraspinatus. We might even take a relatively normal biceps tendon, clip its attachment off the glenoid, anchor the tendon in the groove, and then use the redundant portion to fill the gap in the supraspinatus. (Fig. 52a.) This would give the biceps muscle a fixed origin, and we would at the same time obtain a firm attachment for our supraspinatus. We should only have lost whatever function the long head of the biceps has from having its attachment on the glenoid rather than on the humeral head; i.e., the outer head of the biceps would no longer be of use in motions of the humerus on the scapula, but could still apply its power in flexing the forearm on the humerus. What then is this function which we should lose so far as scapulo-humeral motion is concerned? The function of the biceps muscle is fourfold. First, it is a flexor of the forearm on the humerus. Second, it is one of the flexors (or extensors?) of the whole arm on the scapula; in a sense, therefore, it is a weak abductor or elevator of the arm. Third, the external insertion on the tubercle of the radius enables it to act as a supinator of the radius and hand. Fourth, the long head of the biceps passing through the intertubercular groove helps to retain the head of the bone on the glenoid, and stabilizes the head in the various degrees of rotation, as the arm is elevated. This function is well illustrated by the findings in two of my cases, which at operation showed that except for the subscapularis, the whole of the capsule with the tendons of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus and teres minor had been evulsed, yet the head did not tend to dislocate; apparently it was held in the joint'by the long head of the biceps, and by that only. We lose nothing in the first function, little in the second, none in the third and but a problematic amount in the fourth, by using it in the way suggested in Fig. 52a. So far as the action of the shoulder joint is concerned, particularly with reference to the functions of flexion of the arm on the scapula and of the forearm on the humerus, the origin of the short head of the biceps from the coracoid process is more important than that of the long head from the edge of the glenoid. The coracoid origin is sufficient to give power in these motions; the long head is chiefly a stabilizer and one of secondary use so far as the application of power is concerned. For instance, in cases in which the long head of the biceps is ruptured and no other lesion has occurred, the function of the shoulder remains almost normal. The short rotators are sufficient to maintain the fulcrum on the glenoid in most positions of the arm, but where these short rotators are damaged, I am confident that the long head serves a very useful purpose in guiding the head of the humerus and restraining it from forging upward and getting its fulcrum on the acromion. I therefore regard it as important to keep the long head of the biceps intact if possible. I have notes that in some of my operated cases, the biceps was torn away from its glenoid attachment. In such cases in future I intend to search for the distal end of the tendon and to anchor it with stitches in the bicipital groove, and also to the supraspinatus tendon, thus abandoning any idea of retaining its stabilizing function and being content with retaining its power as a flexor of the forearm. At present I see no good mechanical way of re-attaching it to the glenoid so as to make it function in guiding the head of the humerus as the latter is abducted. One is apt to think of the long head of the biceps moving up and down in the intertubercular groove, but this is not what actually happens. The humerus moves up and down on the tendon; it is not the tendon which moves through the groove. (See Fig. 52.) On the whole, I should say that if the operator finds that the biceps is so damaged that he thinks it will not in future form a smooth cord on which the humerus can ride up and down, he had better use it, as described above, to replace the lost substance in the supraspinatus.

4. What shall we do if we find there is no stub of supraspinatus tendon left on the tuberosity to which we may suture the proximal portion? In long-standing cases we find a tuberosity completely bare of tendinous substance, and perhaps somewhat eroded. Since this tuberosity is useless unless we can suture the tendon to it, it might as well be removed. I have not hitherto excised the tuberosity in cases in which I could not suture, but it might be well to do so. Such an excision would make the surface which must ride under the acromion less apt to cause friction. Nature does exactly this by causing recession of the tuberosity. As a rule I have drilled two holes in the tuberosity with an ordinary shoemaker's awl, and passed a heavy silk suture through these holes and the tendon so as to draw the tendon as nearly as possible to the facet of insertion of the supraspinatus. This can usually be accomplished, but occasionally the supraspinatus is so retracted that I cannot quite draw it down to the bone. I have on several occasions made a sort of plastic so that I covered the suture with part of the roof of the bursa, believing that the repair of the tendon comes not from the tendon itself, but from the adj acent synovial membrane which is much richer in vascular supply.

5. Another operative problem is how to repair the rent. As explained in the chapter on pathology, these rents are in a general way triangular, with the base on the humerus and the apex retracted, the apex being usually the center of the supraspinatus, and the sides the lateral expansions which are united to the neighboring tendons. The ideal way to close would be to bring the center of the apex to the center of the base, but if the retraction is great and the base is small, the triangle is so prolonged upwards that one is tempted to close the gap from side to side until very near the base, and then to make the last suture a triangular stitch. This method is easier, but it does not bring back the normal relations. However, it is a feasible method to use where there is much retraction. The exact way in which to put the sutures does not seem important, that is, whether they are mattress sutures or interrupted or continuous.

6. Formation of a new sulcus. If the reader will refer to Chapter IV, and especially to Plate VI, Figs. 3-4, and their legends concerning the remarkably effective method which nature has devised to attach the supraspinatus tendon to its facet, he will feel great doubt as to whether the surgeon will ever be able to imitate it with any degree of success. We need much study and experimental work before we can rely on being able to create a line of living cement such as the "blue line," with its pores for the finger-like processes. At present, from what we know of histology, it seems doubtful whether in adult life such a method of union of tendon to bone can ever be achieved. However, we know that tendon can form a fairly firm cicatricial attachment to raw bone. What is the best practical way to secure this ?

If it were possible, we should wish to have the new tendon form on the raw surfaces of the sulcus and of the tuberosity down to the actual edge of the joint cartilage. When I drill the tuberosity I try to drill it as far as the cartilage edge, and I usually erode the bone of the sulcus with the point of a knife or curette, so that the tendon will have a little better chance to become attached by granulation. Dr. Philip Wilson has improved on my operation by cutting a slot around the cartilage edge and drilling through the base of the tuberosity. He then passes a slip of fascia lata through the drill holes to be attached above to the supraspinatus. He thus makes a more ideal suture, so that the tendon fills the entire sulcus and thus gains a firm hold on the tuberosity. It remains to be seen whether nature will tolerate such attachments indefinitely.

7. A frictionless surface for the base of the bursa is a most important point. Dr. Wilson's method has this advantage. It would be repetition to discuss this further, but I should like to repeat that even in those cases where the suture at the end of the operation has seemed rough, it may nevertheless be so changed by the healing process that a surface is produced which at a later operation appears smooth and normal.

8. I use silk sutures because I want them to endure long enough for new, strong, scar tissue or tendinous substance to form over them. I use a fairly heavy pedicle silk for the main suture, which passes through the holes in the tuberosity or between the proximal and distal portions of the tendon. I have on four occasions reopened the bursa later to remove these silk stitches because the patient complained of pain. The following are the findings in these four cases:

CASE 18 Mr. R. H. S. Age 60. M. G. H. No. 181765 E. S., Mar. 26, 1912. A typical case of complete rupture of the supraspinatus, one and one-quarter inches wide. Although much retracted, the tendon was caught and sutured in place with three mattress sutures. The functional result was good, but he continued to have more or less pain, apparently from the formation of a considerable amount of dense inflammatory tissue about the site of suture. On Feb. 13,1913, under novocaine, the bursa was again opened and the tendon was found not only completely repaired, but there was a large amount of dense hypertrophic, callous-like tissue about the sutures. This mass impinged on the acromion in abduction; most of it was removed with the scissors and a new opening made through the supraspinatus into the joint, so that some of the synovial fluid could flow into the bursa and lubricate it. The result of this operation has been satisfactory. Twelve years later, on June 9, 1925, he called to see me because of a slight injury to his left shoulder. The right, on which I had operated, had given him no trouble in the intervening years, although he had worked steadily as a coachman.

CASE 29 Mr. M. M. W. Age 39. M. G. H. No. 184216 W. S., Aug. 5, 1912. A clear case of badly ruptured supraspinatus tendon. The tendon was sutured with heavy silk and function was restored. During the following year he had much pain on use of the arm in his work as a laborer. The bursa was again explored and the silk sutures and some of the chronic inflammatory tissues lying about them were removed. I also made a new opening into the true joint to permit the fluid to flow into the bursa. This was followed by improvement but not by complete relief. No late report. Note that entire repair of the rupture had taken place.

CASE 88 Mr. T. M. Age 50+. Operated on at Faulkner Hospital, July 24, 1926, six months after his injury. The supraspinatus, infraspinatus and part of the subscapularis were found to be torn away, exposing the biceps tendon, which was greatly inflamed. There was much fluid in the joint. A very unsatisfactory suture was made, and the tuberosity had to be drilled. The arm was put up in abduction. Mild sepsis occurred and there was much fluid drainage, so that the wound took several weeks to heal. Some of the deep sutures were taken out. In spite of this the result at first was good, and he returned to his work after five months. He worked for a year and three months, although in some pain, and then had another slight injury. On July 2, 1928,1 again explored the bursa and found that most of the sutures had pulled away, leaving the condition practically as bad as at the first operation. This was as bad a result as I have ever had. The patient was for a time benefited, but in the end gained nothing by the operation, for I did not attempt a second suture.

CASE 112 Mr. A. C. Age 62. Operated on at the Trumbull Hospital on June 11, 1928, three months after his injury. A typical complete rupture of the supraspinatus was found and satisfactorily sutured. The immediate result appeared to be good. However, the patient would not go to work again, complained bitterly of pain on use of the arm and became very neurasthenic. On Feb. 7, 1929, I again explored the bursa, thinking that if I took out the deep sutures some of the irritation might be relieved. My notes say: "I operated on him yesterday under novocaine ansesthesia. Dr. B. E. Wood was present and Dr. Stevenson assisted. Incision was made just inside the old scar and the bursa was opened. It was clearly shown that the former suture had been effective in restoring the insertion of the tendon. Moreover, the floor of the bursa was smooth and shiny, and there did not appear to be any cause for friction over the site of the suture. One heavy silk suture could be seen just below the transparent synovial lining of the base of the bursa; this was easily pulled out, but the other two sutures were buried deeply in the new-formed tendon and were found and removed with difficulty, as I was anxious not to weaken the tendon in so doing. In two of the sutures the knots were apparently untied; in one the knot was still present, but almost untied. At first I thought that the knots of the two untied ones had been left behind, but on reflection I think it is more reasonable to suppose that they had become untied as the tissues increased in amount and grew into the knots, which were cut very short. Yet it is possible that they broke off and remained in, although the total amount of silk in the untied ones appears greater than in the tied one by more than double. At any rate, very little silk could have been left behind. "I did not feel satisfied that the silk was causing any trouble, for there appeared to be no inflammation about it, and the tender point of which the patient complained was nearly a half-inch away from the sutures, on the edge of the greater tuberosity close to the bicipital groove. That there was some inflammation at this point was made clear by finding a little crumbly, soft, cheesy tissue close to the synovial sheath of the biceps tendon, which in certain positions bulged slightly. The repair of the tendon was weakest at this point, and I fear that my search for the sutures weakened it still more, although not to an extent sufficient to interfere with function, and recompensed by the finding of this suspicious tissue. Two tiny bits of this tissue were saved for pathologic examination. (Plate V, Fig. 5.) The patient still claimed to be unable to work in January, 1931. Since three out of four cases, which were explored a year or so after the first operation, showed not only firm tendons but hyper-trophied ones, it seems to me that it is proved that suture may be effective. In each case I was surprised to see how well nature had restored the even convexity of the floors of the bursae, which at the completions of the operations had been quite irregular and rough at the suture lines. All four cases, if operated on immediately after their injuries, might have had excellent results; as it was, although two of the four cases had good results, little was gained by the other two patients, unless they may take some satisfaction as demonstrators of the fact that these tendons even when badly broken may be repaired.

9. The shape of the needles is dictated by the shape of the field of operation and by the fact that a tremendous strain is put on them. They must be either fully curved or half curved, not over a half-inch long and with very strong shank and eye. One has to work between the acromion and the tuberosity, where there is very little room, so that even a curved needle such as is used in ordinary operations is too large to be turned about in this space.

10. Shall we close the roof of the bursa or shall we merely close the muscle, leaving the roof of the bursa free to allow the synovial secretions to seep into the areolar tissue? As I have previously stated, there is usually in these cases a considerable synovitis with a large amount of fluid. If the bursa is closed tight, this fluid forms under tension and causes pain. Closure also tends to keep blood in the bursa which would otherwise be washed out by the fluid itself. I prefer the idea of leaving the roof of the bursa unsutured to allow this fluid to escape, but I am not prepared to say positively that it is not better to suture the bursa and allow free motion after the operation to pump fluid out between the stitches. The fact is, in cases where there is much fluid (and these cases are usually those that have continued to work in spite of the friction and pain), the fluid seeps into the soft tissues to an extent which causes marked swelling and sometimes induces an edema and suggestion of sepsis. This used to be a frequent complication when I put the arm in elevation, permitting the lower side of the capsule to be held tense and therefore driving the fluid up toward the wound. Now that I treat them without restraint, I do not have this complication

11. The postoperative treatment. I find that my tendency has been, as the years go by, to allow more motion and to allow it sooner. I usually pad the axilla with a small pillow and then let the arm lie on it in a position a little more abducted than that in which the arm rests in a sling, contriving as best I can to keep the hand away from the front of the abdomen, because the tendency of the patient after these operations is to get the arm in a strongly internally rotated position, and therefore the recovery of the power of external rotation is slow. After the first night is over, I remove the dressing and let the patient put the arm in any comfortable position which he can find. Each day I exercise it in a way which is difficult to describe, but which is a matter of personal touch. The general purpose of the exercises is to let the patient bend his body from the hips with the arm relaxed, as described under the stooping exercises (Fig. 47). As in treating fractures near joints, I try to make the patient do as much active and passive motion of the arm as I believe I can without displacing the fragments. It is impossible to lay down more definite directions, but I may say that by the end of the first week I expect the patient to be able to bend his body at the hips to a right angle, and to let both the injured and well arm fall in a relaxed position at right angles to his body. By twisting his body from side to side so as to make one shoulder higher than the other, alternately, he can also move the joint without contracting the shoulder muscles. During the second week he is encouraged to swing the arms a little in both directions in this stooping position. The wound should be soundly and completely healed and the patient discharged from the hospital in from ten days to two weeks. After that he is encouraged to take the stooping exercises. If the patient is cooperative and understands the mechanics of the operation and can use common sense in taking his exercises, he gets on fairly smoothly, but there is pain of an annoying although not of a serious degree, not only for weeks but for months. I do not think this would be the case where the operation was done immediately after the accident. In convalescence it is a good rule to restrain the patient from exercising his arm in the erect position until he has learned to abduct it freely and strongly in the stooping position. (See Fig. 47.) In long-standing cases the nerves of the region have already become sensitized and are slow in returning to a normal condition. Much of this postoperative soreness in the delayed cases is due to the sensitiveness and synovitis acquired between the date of the injury and that of the operation.

THE SABRE-CUT INCISION

Reprinted from the Bos. Med. & Surg. Jour., Mar. 10, 1927. It does not differ greatly from Kocher's posterior incision, but is more appropriate after a preliminary exploratory cut anterior to the joint.

FIGURE 1

"Sabre-cut" seemed an appropriate name for this incision, for it might well be made by the downward cut of a sabre on top of the shoulder. An incision is made through the acromio-clavicular joint and continued with a saw through the base of the acromion. The anterior point of the incision would be continuous with a previous routine bursal exploratory incision. When the acromion has been sawed through, an epulet of tissue, consisting of the deltoid muscle and the acromion process from which it arises, is formed to be pulled outward and downward. This step is accomplished' with ease, for it is only held by a little areolar tissue and a few fibers of the trapezius attached to the upper margin of the detached portion of the acromion. The upper posterior fibers of the deltoid must be separated a little to gain mobility. In sawing the base of the acromion one must bear in mind the suprascapular nerve which supplies the supra- and infra-spinatus muscles and lies between them, a little below the saw-cut. It is deep enough to be out of the way of the saw but not of gross carelessness.

FIGURE 2

The second diagram shows the structures exposed when this epulet is pulled downward and outward. Even without dissection one can identify the subscapularis, supraspinatus and infraspinatus as they emerge to join together their tendinous expansions beneath the base of the bursa. To one unfamiliar with this dissection the smooth convex surface of this base appears to be the articular surface of the humerus. The subacromial and subcoracoid or coraco-humeral bursse are nicely shown. As explained in previous papers, they are often intercommunicating and are always functionally one bursa although frequently, as in this instance, separated by one of the diaphanous nictitating folds. Notice the separated portion of the acromion and see how easily it will fit back into place.

FIGURE 3

The third diagram is identical with the last except that the supraspinatus and capsule have been cut across into the true joint and the ends of the supraspinatus depicted as retracted. The stub of the tendon is still attached to the tuberosity beneath the base of the bursa, while the muscular belly is retracting into the supraspinatus fossa. The glenoid and the articular surface of the humerus are exposed, with the long head of the biceps arising from the superior edge of the glenoid lying across the cartilaginous surface of the head of the humerus. This is exactly the condition I have found at operation again and again in the living, except that there is seldom so much of a stub of tendon still attached to the tuberosity. Quite frequently it is entirely evulsed from the latter, requiring drilling of the tuberosity to resuture it. I have always found the base of the bursa to be torn across with the tendon. The point of least resistance appears to be about the subbursal portion of the tendon. In fact the tendon itself is very short, the muscle fibers beginning within a half-inch of the attachment. In the long-standing cases on which I have operated the biceps tendon is found inflamed, swollen and bright pink in color, forming a striking contrast with the white articular surface of the humerus. Sometimes it is apparently absent entirely, having been evulsed and then retracted downward into its sheath. To close this incision the parts are sutured back into place in the reverse order of these diagrams. It is probably safer to wire the acromion process, although catgut in the soft parts holds it well. I do not advise attempting to close the bursa even in the exploratory operation; a stitch or two in the muscle holds the edges in sufficient apposition and excess fluid may drain into the areolar tissue.

The pendulum will probably swing in future toward postoperative treatment in abduction and back again to adduction. Dr. Wilson now uses abduction after the sabre-cut incision and complete repair of the insertion into the bone by the use of fascia lata. It is possible that this method has the advantage of creating a larger gap between the head of the humerus and the acromion and the coraco-acromial ligament, because reunion of the mobilized acromion process would take place at a higher level, since it is pressed upward by the abducted humerus.

The Sabre-Cut Incision. Although I have personally given up the sabre-cut incision for cases of rupture of the supraspinatus, it is still used by others, especially by Dr. Wilson. It gives a splendid opportunity to repair the tendon or any other structure in the shoulder joint, but it is really a major operation, while the one I use is a minor one. The main reasons why I seldom use it are three. In the first place, I have learned to work through the routine incision in such a way that I can do the operation without cutting any ligaments or bone. This improvement has come about not only from doing the operation in dorsal flexion, but by using the method of rotating the humerus so that each desired point is placed in the middle of the small incision at the appropriate moment for a stitch. One assistant has to manipulate the arm in unison with the wishes of the surgeon. In the second place, I have found that after division and suture the acromio-clavicular joint may remain somewhat unstable. A third reason is less technical and more in the domain of human nature. In Industrial Surgery there is not a frank understanding between surgeon and patient as in their ordinary professional relation. The patient is apt to have the element of compensation too strongly in mind, as compared to a cooperative tendency to make the best of the surgeon's attempt to better an injured limb, although both know it may never again be "as good as new." The extent of the sabre-cut incision exaggerates in the patient's mind the degree of the injury and the scar would certainly be impressive to a commission or jury.

Frontispiece

RUPTURE OF THE SUPRASPINATUS TENDON

FRONTISPIECE

THANKS to Dr. F. B. Mallory I was able to obtain the autopsy specimen of a case of a completely ruptured supraspinatus, from which this painting was made by Mr. Aitkin. The skin and subcutaneous tissues were removed; then the fibers of the deltoid separated and held apart by retractors as in the usual routine incision. The diamond-shaped area between the two retractors is the floor of a rather large bursa. Nearly the whole right half of this floor retains its normal, smooth, whitish appearance, but in the left-hand portion of the base or floor is a roughly triangular area which represents the gap formed by the retracted supraspinatus tendon. At the right of this triangular gap, the long head of the biceps appears just beneath the falciform edge of the portion of the musculo-tendi-nous cuff formed by the subscapularis. In the left angle of the triangular area is seen a falciform edge formed by some of the superficial fibers of the infraspinatus. Just superior to this are a few vertical fibers of the deep posterior part of the supraspinatus which have not been evulsed. This was a. very thin, tenuous bit of tissue. The remaining central portion is roughly divided into three parts. The upper, bluish third is the exposed cartilage of the true joint. On its shiny surface near the very edge of the true joint cartilage, we see the high light of the reflection of the window. The lower third of this central space shows a typical "volcano" on the tip of the tuberosity, such as those depicted in Plate V, Figure 1, and in Figures 36 and 40. Between this "volcano" and the cartilage, and also occupying about one-third of the central area and bounded on the right by the margin of the biceps tendon, and on the left by the film-like, untorn edges of the infraspinatus and supraspinatus, we see a red, granulation-like irregular surface. This is the pathologically changed facet of insertion of the supraspinatus tendon and of a portion of that of the infraspinatus from which the tendons have been torn. Compare Figure 40, which is the Rontgen picture of the same specimen. It must be understood that this picture represents the result of an injury experienced, in all probability, many years before; the tuberosity is in the recessing stage, and the edges of the torn tendons have become smooth by becoming falciform. The distal stub of the supraspinatus tendon, which was probably present in the first few months after the injury, being functionless, has disappeared. The proximal end of the tendon has retracted upward and could only be demonstrated if the newly formed falciform edge of the whole rent were removed. Even in this old case it could be isolated, pulled down and attached to the tuberosity, although with difficulty. One can readily imagine the pain which this patient endured during the first few years after his injury from the mere mechanical irritation from the tuberosity striking on the edge of the acromion during efforts at elevation of the arm, although nature has gradually nearly smoothed off the former prominent tuberosity, and, by partial healing of the edges of the torn structures, has made a new base of approximately spherical surface to pass under the acromion. The writer's operative efforts have mostly been concerned with relieving the results of such conditions. When the general practitioner has learned to recognize the symptoms of these lesions within a few days of their occurrence, suture of such torn tendons will be easily and successfully accomplished.

Biomechanics of the Posterosuperior Rotator Cuff

A primary function of the rotator cuff is to work synergistically with the deltoid to maintain a balanced force couple about the glenohumeral joint. A force couple is a pair of forces that act on an object and tend to cause it to rotate. For any object to be in equilibrium, the forces must create moments about a center of rotation that are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction. Coronal and transverse plane force couples exist between the subscapularis anteriorly and infraspinatus and teres minor posteriorly. The rotator cuff force across the glenoid provides concavity compression, which creates a stable fulcrum and allows the periscapular muscles to move the humerus around the glenoid.

The rotator cable is a thickening of the rotator cuff that has been likened to a suspension bridge in which force is distributed through cables that are supported by pillars (the anterior and posterior attachments). The anterior rotator cable attachment bifurcates to attach to bone just anterior and posterior to the proximal aspect of the bicipital groove. The posterior attachment comprises the inferior 50% of the infraspinatus. With small central tears the cable attachments often stay intact and forces are transmitted along the rotator cable. The rotator cable also explains why patients with most rotator cuff tears can maintain active forward flexion, and also why even after only a partial rotator cuff repair, good functional results can be achieved.[1]

However, in the setting of massive rotator cuff with rotator cable disruption and non-compensation by other humeral head stabilizers (i.e pectoralis major and latissimus dorsi), the moments created by the opposing muscular forces are insufficient to maintain equilibrium in the coronal plane, resulting in altered kinematics, instability, and ultimately in pseudoparalysis. Interestingly, only few patients with an irreparable rotator cuff tears developed pseudoparalysis and arthritis.This finding has at least two potential explanations. First, the subscapularis that may not be involved in these tears is the key factor of active forward flexion.[2]

Second, the rotator cable, has still an intact anterior attachment which is important for elevation. This may explain why patients can maintain active mobility, and also why even after only a partial rotator cuff repair, good functional results can be achieved.[3]

Consequently, all the conditions for an imbalance in the force couples are not always met and subsequently loss of function is only occasionally seen.

Clinical examination

Supraspinatus

Superior rotator cuff insufficiency, present in complete tears, is usually associated with a positive Jobe manoeuver and decreased strength in the external resistance of the elbow at the side.[4]

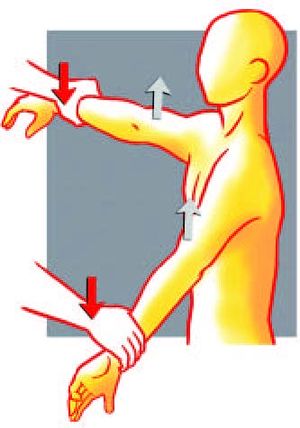

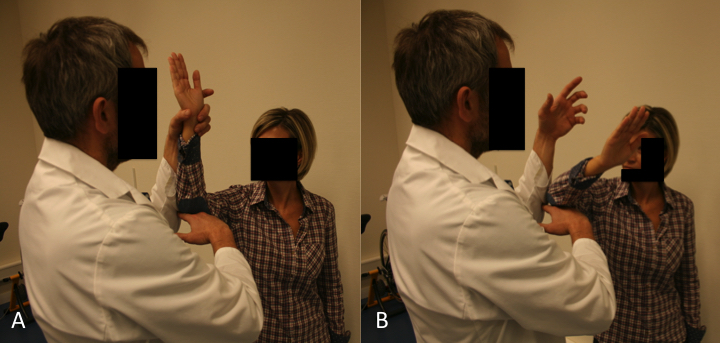

Figure. 1 Jobe manoeuver: the examiner push both arms down at the level of the wrists. Reproduce from Liotard J, Walch G. Test de Jobe. Recherche d'une atteinte du tendon supraépineux. In: Rodineau J, ed. 33 tests incontournables en traumatologie du sport. Paris: Éd. scientifiques; 2009, with permission.

Testing of abduction strength in the champagne toast position, i.e., 30° of abduction, mild external rotation, and 30° of flexion, better isolates the activity of the supraspinatus from the deltoid than Jobe's “empty can” position (Figure).[5]

Infraspinatus and Teres Minor

Strength in External Rotation Elbow at the Side

Strength in external rotation elbow at the side of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus and teres minor represents approximately 10%, 70% and 20% of total external rotation strength, respectively.[6]

However, the function of the teres minor may become more important in the setting of a chronic infraspinatus tear, as its hypertrophy is commonly observed in these cases and probably compensates for external rotation weakness.

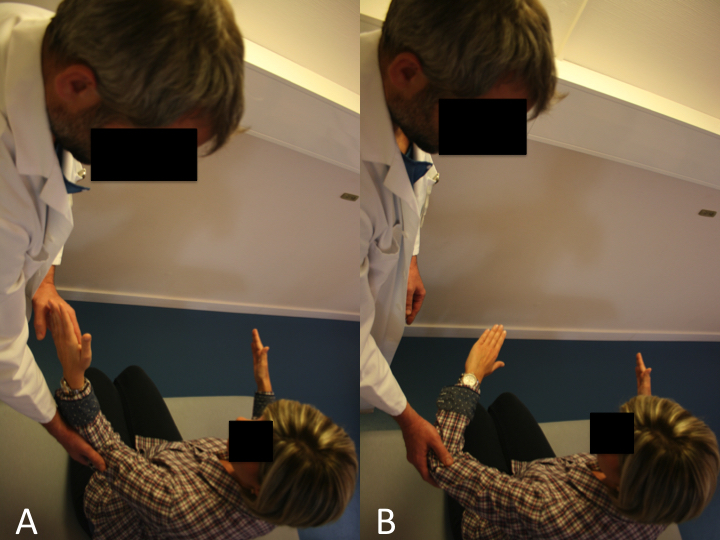

External Rotation Lag Sign

The external rotation lag sign (Figure and Video), described by Hertel, was designed to test the integrity of infraspinatus and supraspinatus tendons.[7]

The extent of internal rotation is recorded to the nearest 10 degrees degrees (10, 20, 30 and 40 degrees or above). An external rotation lag sign > 40 degrees seems to be the most reliable test for the teres minor.[8]

Drop Sign

The drop sign (Figure and Video), also described by Hertel, is designed to assess the function of the infraspinatus.

A) The drop sign is a lag sign beginning from 90 degrees of abduction in the scapular plane, with elbow flexion of 90 degrees, and external rotation of the shoulder to 90 degrees. From this position, the patient is asked to maintain the position against gravity (MRC Grade 3).

B) Failure to resist gravity and internal rotation of the arm is considered a positive drop sign. Reproduce from Collin et al., with permission.

Hornblower sign

The patient is asked to bring both hands to his mouth, but is unable to do so without abducting the affected arm (Video).

Patte Test

The Patte test (Figure and Video) is the only test that allowed to analyze the muscular strength of the teres minor in case of deficient infraspinatus.[9]

A) The Patte test is performed by passively taking from a starting point of 90 degrees of abduction in the scapular plane, an elbow flexion of 90 degrees without external rotation.

B) The patient is asked to perform external rotation of the shoulder from this position against resistance. A positive Patte test is defined as external rotation power less than MRC Grade 4. Reproduce from Collin et al., with permission.

Walch et al. reported a 100% sensitivity and 93% specificity with the Patte test and teres minor fatty atrophy Grade 3 or greater.[10]

Dropping Sign

The dropping sign of Neer had a 100% sensitivity and 66% specificity for teres minor involvement.[11][12]

Imaging

X-rays

The analysis should always begin with plain radiographic views to determine the morphology and status of the glenohumeral joint to exclude glenohumeral arthritis:

Anteroposterior True anteroposterior X-ray with the arm in neutral rotation, and the patient relaxed is obtained to evaluate the shape of the acromion and greater tuberosity, the critical shoulder angle, and the acromiohumeral distance. A decreased acromiohumeral distance < 7 mm in a standard antero-posterior radiograph indicates superior migration of the humeral head which increases the probability of finding an irreparable cuff tear. Such distance is correlated to 1) tears of the infraspinatus that mainly acts in lowering the humeral head, and 2) varying degrees of fatty infiltration.[13][14]

Nevertheless, such criteria should be interpreted with parsimony. First, it is difficult in clinical practice to obtain standardized X-rays making measurement aleatory. Second, this distance has not been associated with an inability to obtain an intra-operative complete repair of the supraspinatus (18.2% irreparable, OR = 0.55, P = 0.610).[15]

At the end of the spectrum, acetabularization of the acromion and femoralization of the humeral head are pre-operative adapting factors reflecting significant chronic static superior instability and are a contraindication for repair.

Lateral Y-view (Lamy)

Lateral Y-view (Lamy) is used to analyze the presence of a spur, the shape of the acromion on this view is less accurate to detect full-thickness rotator cuff tear.[16]

Axillary lateral

An axillary lateral view can exclude static anterior subluxation or os acromialis.

If pathology of the acromioclavicular joint is suspected, a Zanca view is additionally acquired.[17]

Ultrasound (US)

Following X-ray evaluation, advanced imaging modalities are obtained to confirm and plan treatment. Ultrasonography is an excellent cost-effective screening tool in the office but does not allow evaluation of intra-articular pathology or easy evaluation of muscle quality.

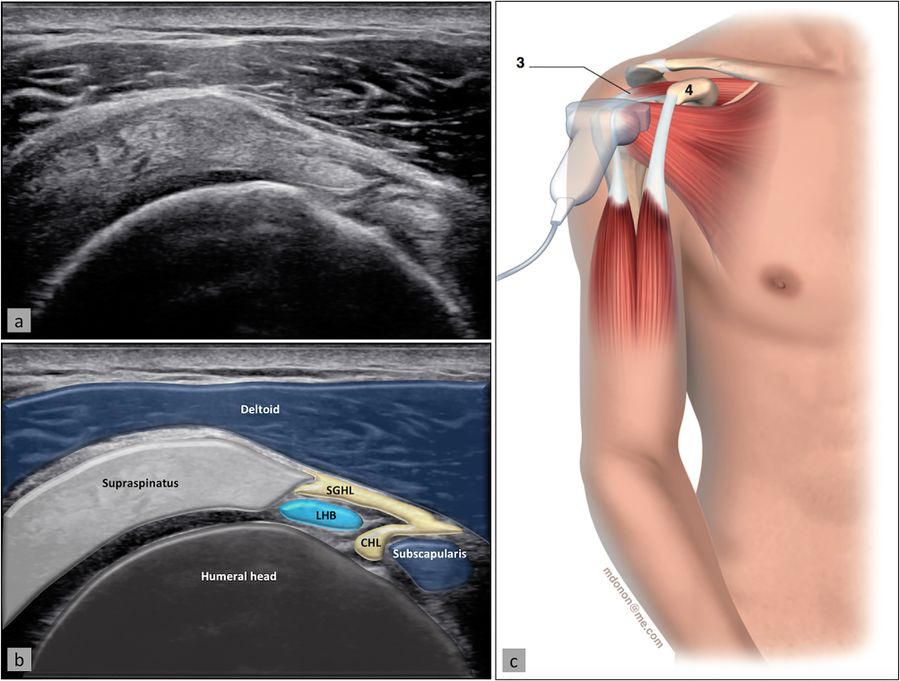

Rotator Cuff Interval

The space through which the long head of the biceps passes as it leaves the glenohumeral joint is called the rotator cuff interval. The patient position is the same as for evaluation of the long head of the biceps, with the probe being placed slightly superiorly to the bicipital groove and in the axial plane (Figure). The long head of the biceps is thus visualized with the subscapularis medially and the supraspinatus laterally, while the coracohumeral and superior glenohumeral ligaments surround it.[18]

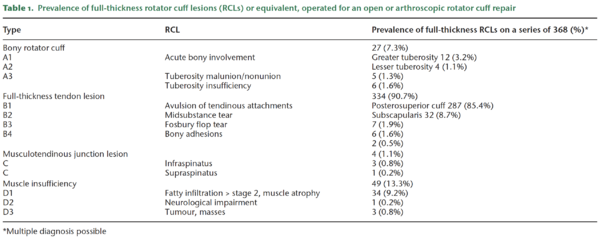

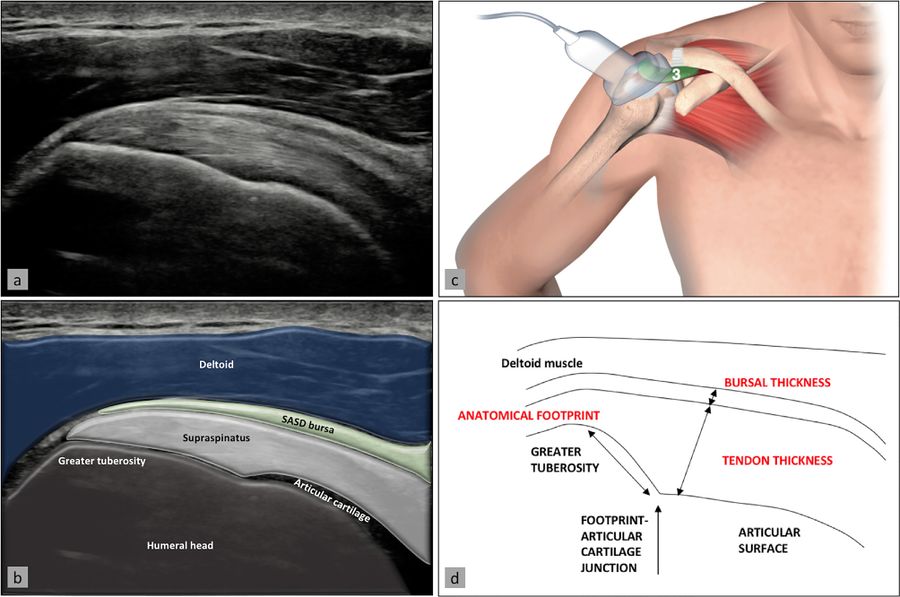

Supraspinatus Tendon and Subacromial-Subdeltoid Bursa

The supraspinatus tendon is best visualized with the shoulder in abduction and internal rotation, by asking the patient to place the palm of their hand on their back pocket, elbow pointed backwards (Figure). In patients presenting with reduced range of motion (adhesive capsulitis for example), maximal internal rotation with the arm hanging by the side of the thorax can be sufficient. The long axis of the tendon is most useful for analyzing integrity of the tendon on the footprint (measuring approx. 2 cm medially to laterally), and is visualized by holding the probe in a tilted position (therefore not a true coronal plane but at an approx. 45 degree angle, following the line of the humerus (Figure)).

This position also allows visualization of two other structures: the subacromial-subdeltoid bursa (and the presence of excessive liquid, see below) and the humeral head along with its articular cartilage (and possible surface defects). In the axial plane (again not truly axial but at 90 degrees to the previous plane), the leading edge of the supraspinatus can be identified laterally to the biceps tendon. Moving the probe laterally will reveal the mid-portion of the tendon, with the anterior part of the infraspinatus eventually coming into view as an anisotropic and dark image (as the fibers run in a different plane).

Ultrasound image (a) with superimposed anatomy (b), patient/probe position (c), and landmarks for measurement of these two structures (d). Reproduced from Plomb-Holmes et al., with permission

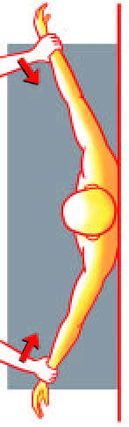

Infraspinatus and teres minor tendon, glenohumeral joint, spinoglenoid notch

The infraspinatus tendon, which inserts posteriorly to the supraspinatus tendon, is best examined in its long axis by elongating it (the patient placing his or her hand on the opposite shoulder) and placing the probe on the posterior part of the patient’s shoulder (Figure). The insertion of the tendon on the humeral head can be analyzed, as well as the musculotendinous junction by sliding the probe medially. At this point, the glenohumeral joint line and posterior labrum can be visualized in thin patients, and even more medially, the spinoglenoid notch containing the suprascapular neurovascular bundle (and the possible presence of a ganglion cyst arising from the posterior labrum which can compress the bundle) (Figure). The teres minor tendon can be difficult to separate from the infraspinatus tendon; it is located inferiorly and has a similar aspect, but can be distinguished by the fact that deeper to it lies bone whereas the infraspinatus lies on articular cartilage, and its insertion is primarily muscular (vs. tendinous).

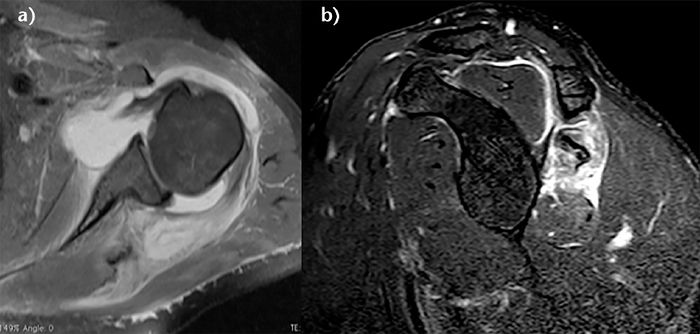

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Computer Tomography (CT)

Magnetic resonance imaging accurately estimates tear pattern, muscle fatty infiltration and atrophy, tendon length and retraction, and is thus obtained to plan repair or reconstructive surgeries. The muscle bellies of the rotator cuff are assessed, if available, on T1-weighted axial, coronal, sagittal views with cuts sufficiently medial on the scapula to allow proper assessment regardless of retraction. Finally, computer tomography (CT) scans are used if magnetic resonance imaging is contraindicated or if joint replacement is planned, particularly in the setting of glenoid deformity. Additionally, computer tomography (CT) scan can be conducted with intra-articular contrast to assess the cuff. It should be noted that the magnetic resonance imaging and computer tomography are not reliable to analyze the acromiohumeral distance as they are performed in lying position.

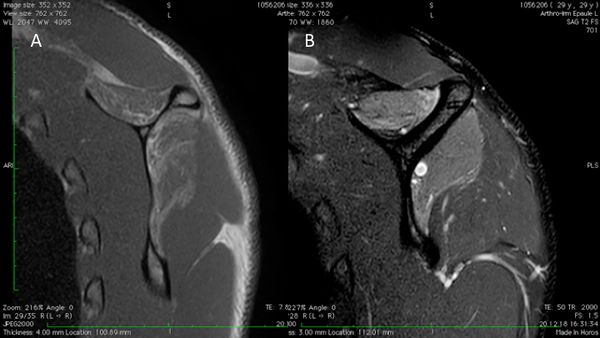

Fatty Infiltration

The most important negative prognostic factor is high-grade fatty infiltration of the rotator cuff muscle bellies (grade 3 or 4 fatty infiltration) (Figure).

Fatty infiltration is irreversible even with repair and leads to reduced function of the rotator cuff musculature.[19]

If pathology of the acromioclavicular joint is suspected, a Zanca view is additionally acquired.[20][21][22]

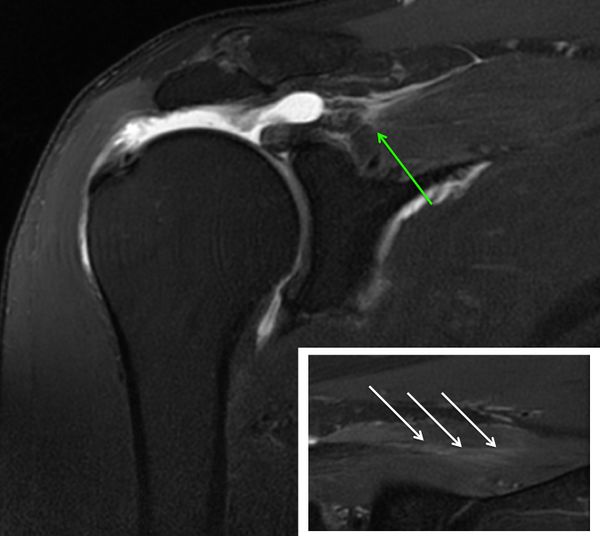

Atrophy

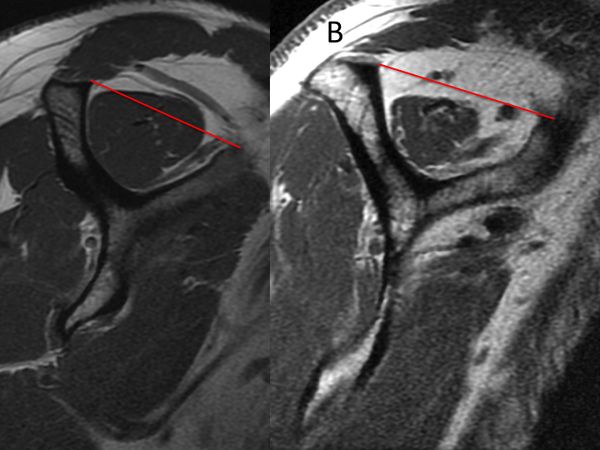

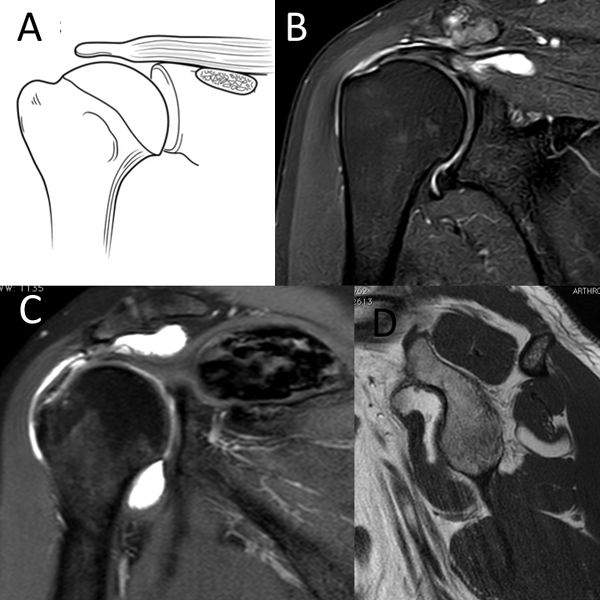

The presence or absence of supraspinatus atrophy is determined using the tangent sign of Zanetti et al. (Figure).[23]

This sign is an indicator of advanced fatty infiltration and has been reported to be a predictor of whether a rotator cuff tear will be reparable.[24][25]

An inability to obtain a complete repair of the supraspinatus is associated with a positive tangent sign (30% irreparable) versus a negative tangent sign (6.3% irreparable, OR = 6,3, P =0.0102).[26]

Supraspinatus atrophy can also be determine according to Thomazeau classification.[27]

Agreement for this classification is however fair (intra-observer kappa = 0,51 and inter-observer kappa = 0.30) and its use cannot be recommended as a criteria of reparability.[28]

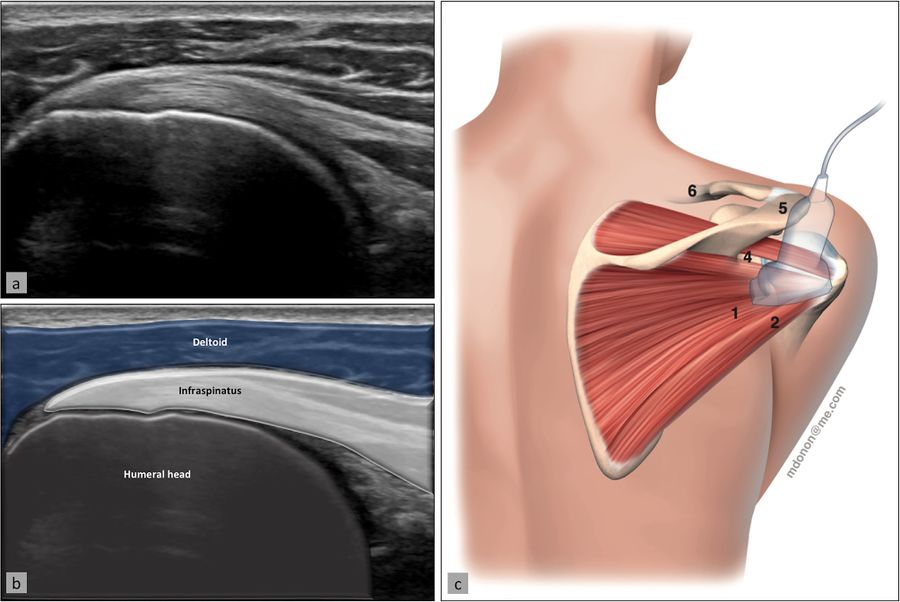

Classification

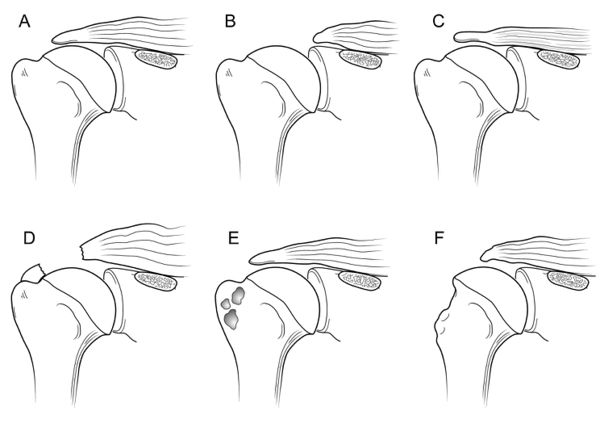

Reproduced from Lädermann A, Burkhart SS, Hoffmeyer P, et al. Classification of full-thickness rotator cuff lesions: a review. EFORT Open Rev 2016;1:420-30, with permission

The rotator cuff lesions are categorized into four major groups based on involvement of the bone (Type A), tendon (Type B), musculotendinous junction (Type C) or muscle insufficiency (Type D).

Type A: Bony Involvement

While the majority of rotator cuff lesions involve the tendinous insertion, bony involvement is an important consideration. Bony involvement includes acute fractures, malunion/nonunion, and chronic bony insufficiency.

A1. Acute Bony Involvement (Fractures and Avulsions)

Isolated greater tuberosity fractures are considered uncommon, representing less than 5% of all operatively treated proximal humeral fractures.[29]

Isolated lesser tuberosity fractures are generally considered rare. Type A lesion of the greater or lesser tuberosity represent approximately 3.2% and 1.1% respectively of surgically treated rotator cuff lesions (Table). Tuberosity fractures are included in the accepted classification for proximal humeral fractures by Neer, in itself a modification of Codman’s original description. Because the greater and lesser tuberosity are the insertion site of the rotator cuff, even small tuberosity fractures or avulsions can represent substantial disruption of the rotator cuff and lead to functional impairment if displaced and left untreated. Historically, Neer proposed 10 mm of displacement as a threshold for operative intervention.[30]

However, more recent investigation has recommended that a threshold of 5 mm31 should be used.[31]

Displacement of greater than 5 mm can lead to bony impingement with loss of range of motion as well as loss of strength from compromise in the normal length–tension relationship of the rotator cuff. A traumatic mechanism is typical such as violent muscular contraction, impaction of the greater tuberosity beneath the acromion, or shearing against the anterior glenoid rim during a glenohumeral dislocation event. Thorough patient evaluation is required to make an appropriate treatment recommendation. Conservative therapy is limited to non- or minimally-displaced fractures. The ongoing development of arthroscopic techniques has led to multiple reports about arthroscopically assisted or total arthroscopic techniques in the treatment of these injuries.[32]

A.2 Tuberosity Malunion/Nonunion

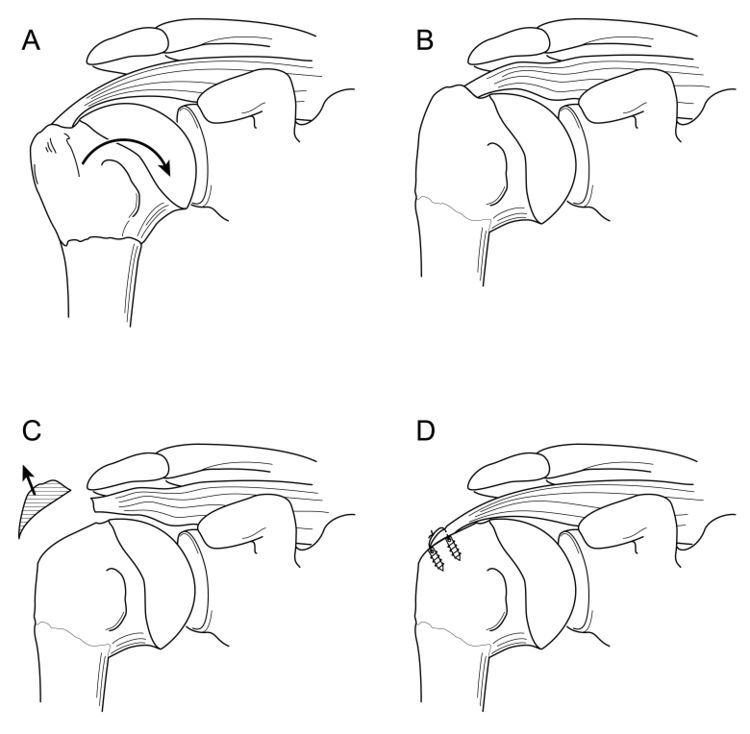

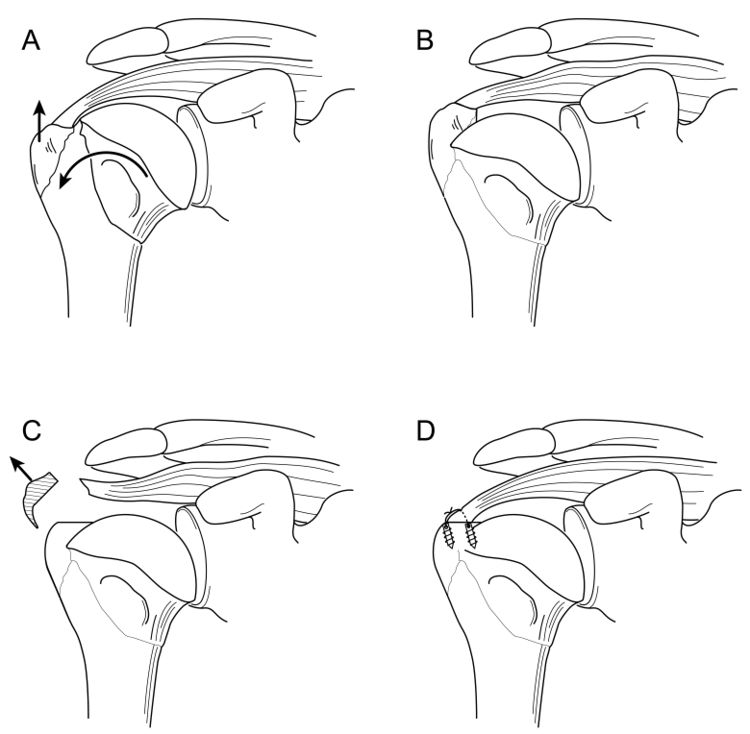

Tuberosity malunion or nonunion can be a sequela of either conservative treatment or surgical treatment of acute injuries. As noted previously, displacement effectively shortens the muscle-tendon unit such that the rotator cuff cannot function properly (Figures).

Various open techniques have been described for the management of the malunion of proximal humeral fractures, including prosthetic reconstruction, open corrective osteotomy, or arthroscopic capsular release followed by takedown of the rotator cuff from the malunited proximal humerus, tuberoplasty, and then rotator cuff advancement. Although the latter technique is technically demanding, it allows preservation of the native humeral head, which is associated with a low complication rate, and avoids concerns about long-term prosthetic survival in young patients (Video).[33][34]

Operative Technique

The patient was placed in a beach chair or in a lateral decubitus position. A diagnostic arthroscopy is performed with an arthroscopic pump maintaining pressure at 50 mm Hg. The joint surfaces were inspected to rule out any incongruities. The articular side of the rotator cuff is carefully assessed with a probe searching for tears. Any capsular retraction is addressed at this point. A release of the rotator interval and superior glenohumeral ligament is performed with an electrocautery introduced from an anterior portal. This was followed by a release of the posterior, inferior, and anterior capsule 5 mm away from the labrum with an electrocautery introduced from the posterior portal while the surgeon is viewing from an anterosuperolateral portal. If still present, the intra articular part of the long head of the biceps tendon undergo either tenotomy or tenodesis. After treatment of any intra-articular pathology, such as loose body removal, attention is turned to the subacromial space.

The lateral and posterolateral gutters are cleared. ny previously placed metal hardware are removed. While the surgeon is viewing from a posterior glenohumeral portal, the tuberoplasty is initiated. The arthroscope is then moved to the subacromial space, and the rotator cuff, if necessary, is sharply elevated from its malunited footprint by use of an electrocautery. Elevation of the rotator cuff consisted of the supraspinatus and anterior half of the infraspinatus, which is the part that overlies the proximally migrated tuberosity (Video).

After elevation of the rotator cuff attachments, a burr is used to perform a tuberoplasty. The cuff is assessed for mobility and integrity and is then retensioned by advancing the cuff laterally on the greater tuberosity and performing a rotator cuff repair. The rotator cuff is advanced and repaired. A modified acromioplasty with a lateral bevel is routinely performed if not done previously.

A.3 Tuberosity Insufficiency

Tuberosity insufficiency can range from contained cystic bony defects within the tuberosity to the absence of the entire tuberosity. Cystic bony defects are often encountered during primary or revision rotator cuff repair. Such defects may be idiopathic, related to a patient's rotator cuff disease, or secondary to osteolysis from breakdown of bioreabsorbable anchors. These osseous defects reduce biological healing capacity and may decrease repair fixation strength. Bone grafting techniques are needed to address these defects.[35]

In such a situation, a simple tendon rotator repair is usually unsuccessful, as a large bony defect significantly lowers the prognosis for primary repair.[36]

One explanation might be that deltoid tension and therefore function is potentiated by the greater tuberosity, also called “deltoid wrapping”.[37]

Therefore, reconstruction of this combined bony and tendon defect may require both tendinous and bony reconstruction. In older patients, such insufficiency is most reliably addressed with reverse shoulder arthroplasty. However, reverse shoulder arthroplasty is not ideal for young patients as multiple studies have demonstrated increased complications in this patient population.[38][39]

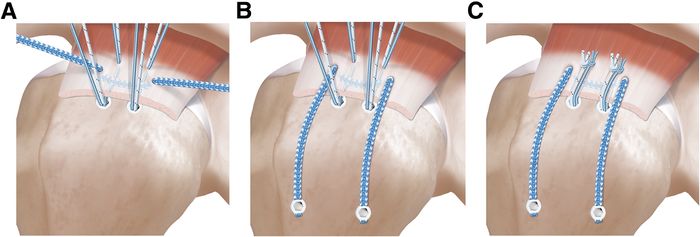

Recently, a fresh frozen bony-tendinous allograft of the calcaneus and Achilles tendon has been proposed to address this difficult problem (Video). Long term results and larger series need to confirm this technique.[40]

Surgical Technique

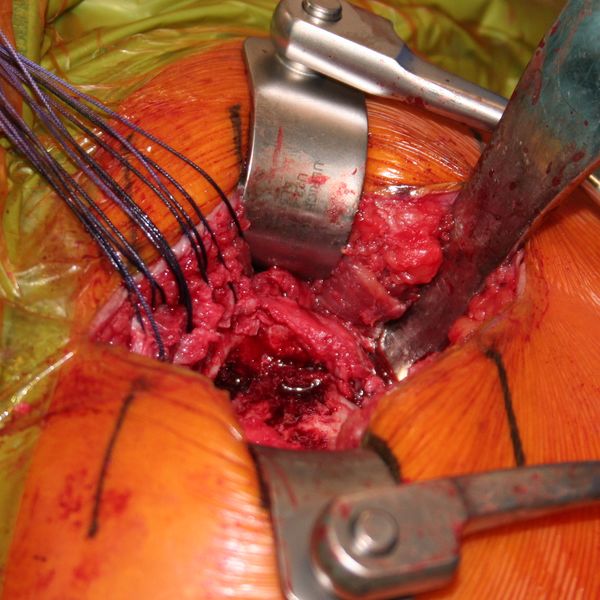

Allograft Reconstruction with Calcaneum and Achilles Tendon for an Irreparable Massive Rotator Cuff Tear with Bony Deficiency of the Greater Tuberosity (Video). Under general anesthesia and interscalene nerve block, the patient is placed in the beach chair position, with the operative arm draped free. An open anterosuperior incision with a deltoid split is performed in order to expose the greater tuberosity defect. The long head of the biceps was already resected. The remaining posterosuperior rotator cuff was carefully dissected and the proximal humeral head is debrided. The quality of cuff tissue is usually poor (Figure).

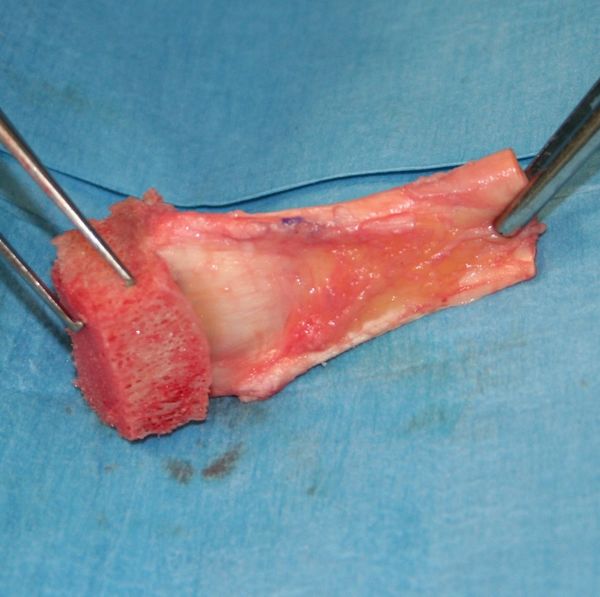

The Achilles tendon allograft with attached calcaneus is then prepared (Figure and Video).

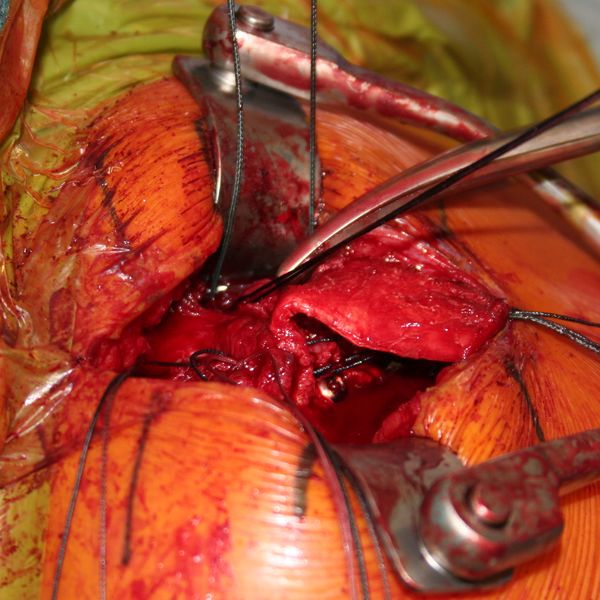

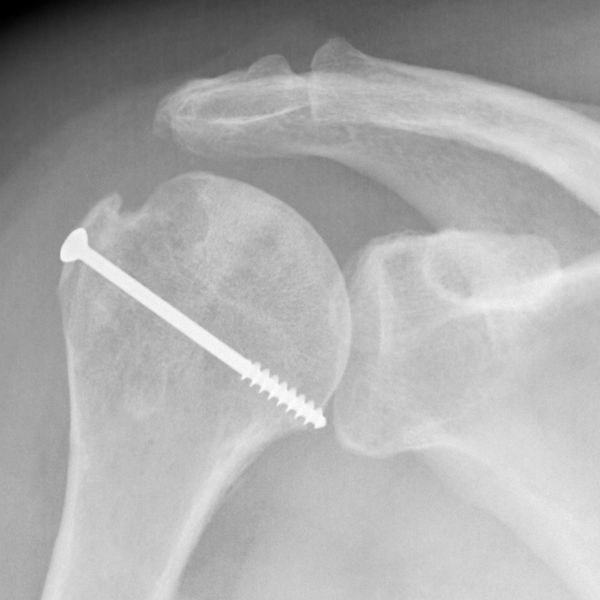

The calcaneus is shaped to fill proximal humeral head defect. If necessary, the Achilles tendon is then split longitudinally to decrease its thickness, with the deep layer used to reinforce the rotator cuff repair. Then, the bony portion of the allograft is secured to the humeral head with a 4 mm malleolar screw under fluoroscopic control (Figure).

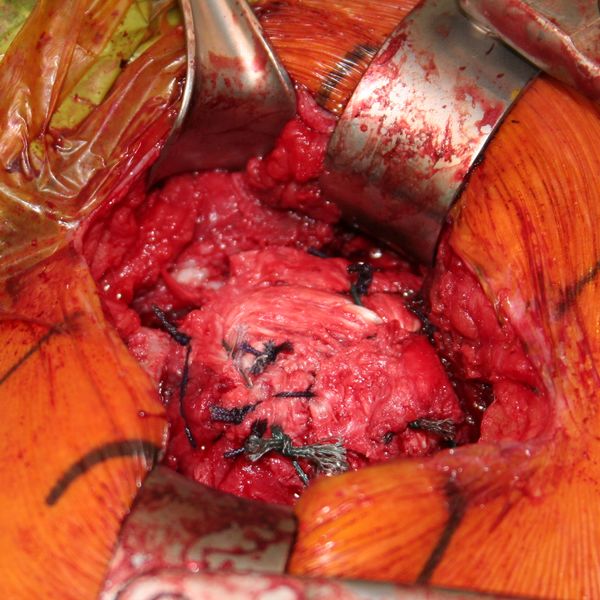

The native rotator cuff was then repaired onto the bony graft with a combination of an anchor and bone tunnels in the graft. The deep split of Achilles tendon is then sewn into the native posterosuperior rotator cuff to reinforce the repair (Figures and Video).

Two years follow-up confirm bony and tendinous integration (Figures).

Postoperatively, the patient wears an abduction pillow for six weeks and is allowed to perform pendulum exercises. After six weeks the abduction pillow is discontinued and passive mobilization is allowed. Full activity return and strengthening was permitted at three months, with a progressive increase of loads.

Type B: Full Thickness Tendon Lesion

B1: Lateral tendinous disruption

Full thickness disruption of the lateral tendon stump is the most frequent type of rotator cuff lesion, comprising approximately 90.1% of all surgically treated lesions (Table). Tendinous lesions most commonly involve the posterosuperior cuff. Subscapularis tears are nevertheless found in 59% of arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs.41 However, such tears are only full-thickness in 8.7% of cases, and are rarely isolated (Table).

Size of Tendon Lesion

Classifications for tear size include measurement in centimeters or number of tendons involved. This information can be derived from arthroscopy or magnetic resonance imaging and used to offer guidance on treatment and prognosis.[41][42][43][44][45]

Once size is identified and if massive, it can be further classified according to Collin et al.[46]

Tendon Retraction

Patte devised a method of classifying tendon coronal retraction that is often used for research purposes.[47]

The retraction is due to tendon and muscle shortening that are not synchronous after tendon tear.[48]

Substance loss in the later stages of musculotendinous retraction may be because of either active shortening of the tendon substance, suggesting that overreduction and lateral transposition of the tendon over the greater tuberosity may be unphysiological.

Tear Pattern

Full-thickness posterosuperior tears come in a variety of patterns. The most common categories include crescent tears, L and reverse L-shaped tears, and U-shaped tears accounting for respectively 40%, 30% and 15% of posterosuperior rotator cuff lesions.[49]

Recognition of these tear patterns is most useful for anatomic restoration during repair. Crescent tears have good medial to lateral mobility and are amenable to a double-row repair. Longitudinal tears (L and reverse L-shaped tears, and U-shaped tears) have greater mobility in 1 plane and typically require margin convergence to achieve complete repair. Finally, massive contracted tears have also been described. These tears have limited medial to lateral and anterior to posterior mobility and typically require advanced mobilization techniques (i.e. interval slides) to achieve repair.

Releases for the Rotator Cuff

In clinical practice, rotator cuff tears may present with a wide spectrum of size and mobility. Many massive rotator cuff tears may be reparable without releases and, in contrast, some small rotator cuff tears may require releases. Release is only required if tear may not be reduced to the footprint anatomically as it would otherwise unnecessarily increase the complexity of the procedure. Releases may be divided into bursal sided releases, articular sided releases (i.e. capsular release) and interval slides.

Double-Row Versus Single-Row Cuff Repair

Biomechanical testing has consistently demonstrated the superiority of double-row constructs.[50]

Within the domain of level I mid-term and short-term studies, double-row repair (Video) showed significant better UCLA score only (American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES), Constant, WORC, and SANE scores showed no significance). This may correlate weakly with the significant lower partial-thickness retear rates of double-row repairs. In contrary, long-term level III studies showed a direct correlation of both functional outcomes and cuff structural integrity, with significant superiority of double-row over single-row repair techniques.[51]

Margin Convergence

Margin convergence to bone can be used in L or V tears. This technique accomplishes margin convergence between the two leaves of the cuff, and at the same time it anchors the cuff to bone, providing very secure fixation. Margin convergence to bone has the mechanical strain reduction advantage of margin convergence coupled with strong fixation to bone. This provides a very secure component to the overall fixation construct.

Load Sharing Rip Stop Construct

Double- row repair is not possible in the setting of medially based tears, lateral tendon loss, or limited tendon mobility. Load sharing rip stop constructs demonstrated improved functional outcomes with reasonable healing rates in an otherwise challenging subset of rotator cuff tears.[52]

This suture technique combines the advantages of a rip stop suture tape and load sharing properties of a double-row repair and has biomechanically superior properties compared to a single-row repair (Figure and Video).[53]

Massive Posterosuperior Rotator Cuff Tears

Prevalence

Massive rotator cuff tears comprise approximately 20% of all cuff tears and 80% of recurrent tears.[54][55]

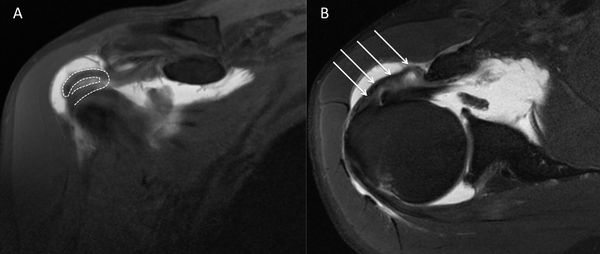

Definition and Classification of Massive Rotator Cuff Tears

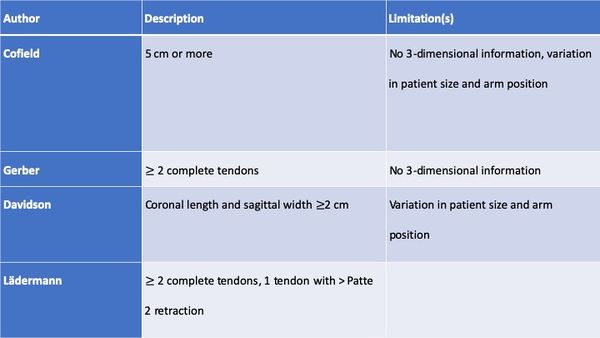

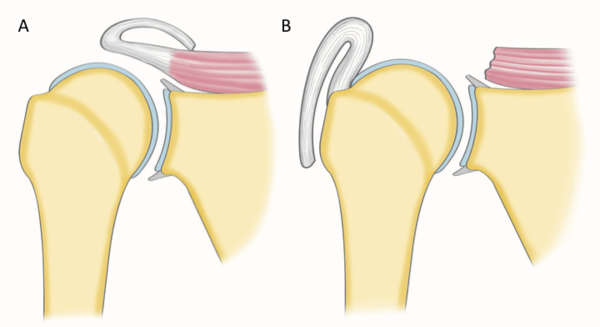

Historically a massive rotator cuff tear has been described as a tear with a diameter of 5 cm or more as described by Cofield or as a complete tear of two or more tendons as described by Gerber (Figure).[56][57]

The former in particular is usually applied at the time of surgery. In an attempt to provide a preoperative MRI-based classification, Davidson et al. defined a massive tear as one with a coronal length and sagittal width greater than or equal to 2 cm.[58]

Unfortunately, these systems are vulnerable to error due to variation in patient size and arm position at the time of measurement. It is more appropriate to define the size of a tear in terms of the amount of tendon that has been detached from the tuberosities. While the Gerber definition helps account for variability in size, there are exceptions to the complete two tendons requirement and this classification does not distinguish different patterns or predict function. Additionally, in using the term “massive”, there is a connotation of difficulty and irreparability. While challenging, most massive rotator cuff tears are reparable and other factors like the tendon retraction, atrophy, arthritis, and mobilization must be considered. Thus, in addition to the number of tendons involved, some authors proposed at least one of the two tendons must be retracted beyond the top of the humeral head (i.e Patte 3 for the supraspinatus in the coronal plane).[59]

Such classification also takes advantage of 3-dimensional information on tear pattern, providing guidance on treatment technique.

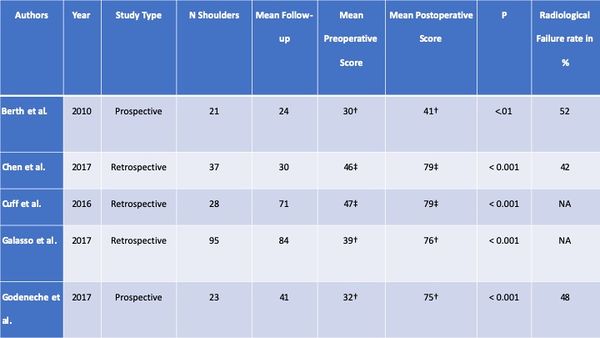

Table: Different Classification of Massive Rotator Cuff Tears

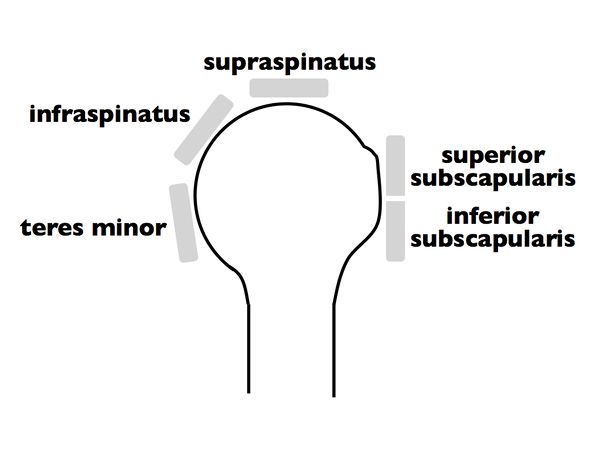

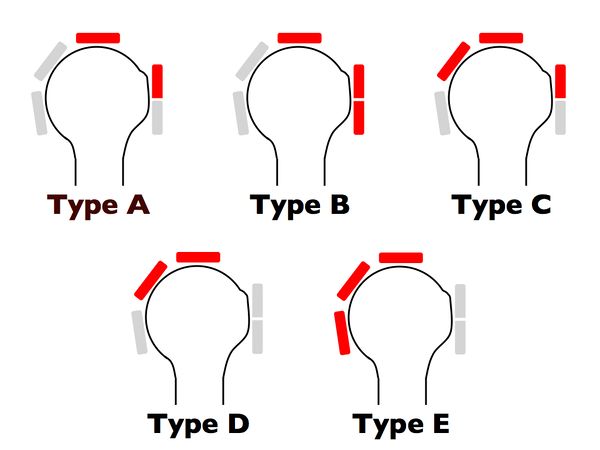

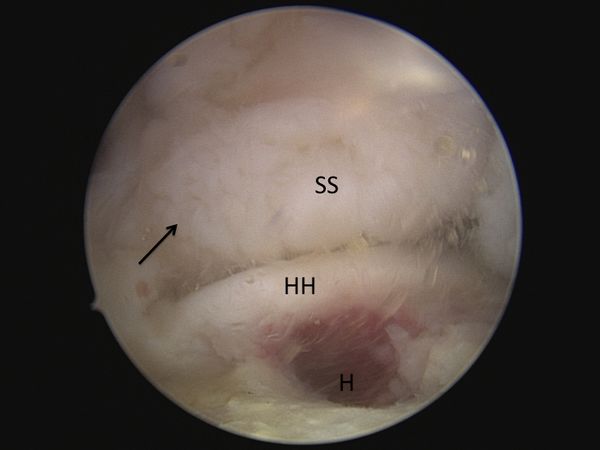

Once a massive rotator cuff tear is identified, it can be further classified according to Collin et al.2 In this subclassification, the rotator cuff is divided into five components: supraspinatus, superior subscapularis, inferior subscapularis, infraspinatus, and teres minor (Figure).

Rotator cuff tear patterns can then be classified into 5 types: type A, supraspinatus and superior subscapularis tears; type B, supraspinatus and entire subscapularis tears; type C, supraspinatus, superior subscapularis, and infraspinatus tears; type D, supraspinatus and infraspinatus tears; and type E, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor tears (Figure).[60]

This classification not only subclassifies massive tears but has also been linked to function, particularly the maintenance of active elevation, offering more information than the traditional six sagittal segments of Patte’s classification.

Suprascapular Nerve Neuropathy and Massive Rotator Cuff Tear

Recently there has been growing interest in the relationship between suprascapular neuropathy and massive rotator cuff tears. Theoretically, medial retraction of posterosuperior rotator cuff tears can place excessive traction on the suprascapular nerve.[61]

However, clinical diagnosis is beset with uncertainties as the potential symptoms of suprascapular nerve neuropathy, namely, pain, weakness, and atrophy, are inseparable from those of massive rotator cuff tear. There is actually no support for routine suprascapular nerve release when repair is performed for several reasons. First, it is clearly demonstrated that repair of repair without release leads to satisfactory results. Moreover, the prevalence of suprascapular nerve neuropathy in case of massive rotator cuff tears in a prospective study is low (2%).[62]

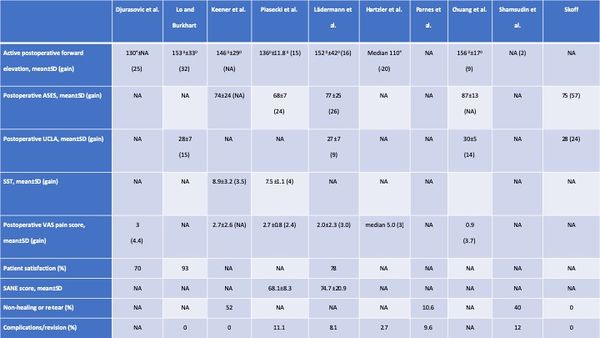

Treatment Options for Massive Rotator Cuffs

It should be remembered that nonoperative treatment is successful in many cases. When surgery is indicated, the primary aim is restoration of force couples and anatomic or partial repair of the rotator cuff to its footprint. However, a number of factors (refusal of the patient, biologic factors, characteristics of the tear, etc) can make these goals difficult, impossible, or unwanted to achieve. Fatty infiltration, rotator cuff retraction, and poor tendon compliance are common in patients with massive rotator cuff tears. In these situations, other approaches have been advocated, with varying degrees of success.[63]

These include physical therapy,59,60 subacromial decompression and palliative biceps tenotomy (subacromial debridement),61 muscle transfer,62 and reverse shoulder arthroplasty.63 However, there are no randomized controlled trials comparing these various options and recommendations are mainly based on retrospective case series and the surgeon’s own experiences.[64][65][66][67][68]

Conservative Treatment

Many patients with massive rotator cuff tears respond favorably to nonsurgical treatment. Nevertheless, patients must be aware that despite clinical improvement, future treatment may be impacted by progression of glenohumeral osteoarthritis and fatty infiltration as well as narrowing of the acromiohumeral distance. In a series of 19 patients with massive rotator cuff tears treated nonoperatively the average Constant score was 83% at a mean follow-up of 48 months. However, 50% of “reparable” tears became “irreparable” during this period.[69]

The mainstay of nonoperative treatment includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, subacromial corticosteroid injections, and physical therapy. The protocol of rehabilitation focused habitually on global deltoid reconditioning and periscapular strengthening. Although certain authors proposed that re-education of the anterior deltoid muscle to compensate for a deficient rotator cuff is the cornerstone, we attach more importance to solicitation of stabilizing muscles of the glenohumeral joint with an approach based on exercises in high position. In this position, the deltoid, which acts synergistically with the remaining rotator muscles, has no upward component and participates in the articular coaptation.[70]